Cloud Architect vs Software Engineer: Roles, Skills, and Career Fit

Choosing between a cloud architect and a software engineer affects how systems are designed, how teams operate, and how products scale in production. Both roles play a critical part in modern engineering organizations, but they solve distinct problems and require different strengths. For technical professionals and decision-makers, the distinction can be subtle until real project complexity exposes it.

According to CloudZero’s cloud computing market snapshot, more than 94% of organizations with over 1,000 employees run a significant portion of their workloads in the cloud, underscoring how central cloud expertise has become to software delivery.

This article breaks down the comparison from a practical, engineering-focused perspective. You will learn how the roles differ in system ownership and daily responsibilities, how skills and tools map to real delivery outcomes, how both roles collaborate in engineering teams, and how to decide which path aligns with your background and goals.

Cloud Architect vs Software Engineer role comparison at a glance

Many organizations use these titles interchangeably, but in production environments they represent different types of ownership and risk. If you are evaluating a career path or defining responsibilities inside an engineering team, understanding this distinction early helps avoid confusion in system design, delivery planning, and long-term operations.

Some organizations also use the terms cloud architect and cloud engineer inconsistently. In this article, cloud architect refers to the role responsible for platform and infrastructure design decisions at the system level.

This section provides a high-level comparison before moving into deeper technical and organizational details.

Primary responsibilities of cloud architects vs software engineers

At a basic level, the difference comes down to what must remain correct and reliable over time in a production system.

Cloud Architects

Cloud architects are responsible for the structure and behavior of the platform that software runs on. Their work defines how services are connected, how traffic flows, how failures are isolated, and how environments are secured.

They make decisions about cloud services, network design, identity management, deployment models, and disaster recovery. These choices determine whether systems can scale safely, meet compliance requirements, and operate within performance and cost constraints.

These responsibilities align closely with modern cloud architecture practices used to structure large-scale production systems.

Software Engineers

Software engineers are responsible for the behavior and quality of the software itself. Their work defines how applications process data, expose APIs, enforce business rules, and respond to users and other systems.

They design and implement features, maintain codebases, fix defects, and evolve systems over time. Their decisions determine whether functionality is correct, changes are safe to deploy, and technical debt remains manageable.

In most organizations, this work is delivered through structured software development services that support long-term application maintenance

How cloud architects and software engineers differ in real projects

In small applications, the same person may design infrastructure and write application code. As systems grow, these responsibilities separate naturally.

Cloud architects focus on platform-level concerns such as multi-region deployments, service isolation, network boundaries, and operational visibility. Software engineers focus on delivering features, improving performance within the application layer, and integrating with external services.

The distinction becomes especially visible in distributed systems, regulated industries, and products with strict availability requirements, where infrastructure design decisions directly affect how safely application changes can be released.

These environments often rely on established cloud-native design patterns to manage service boundaries and operational complexity. In smaller teams, these responsibilities may be handled by the same person, but the underlying concerns remain distinct.

When you need a cloud architect or a software engineer

Cloud architects become especially important when:

Systems span multiple services or environments

High availability and disaster recovery are mandatory

Security or compliance constraints shape infrastructure design

Cloud spending and capacity planning become material concerns

Organizations at this stage often bring in experienced cloud infrastructure developers to guide platform design and reliability planning.

Software engineers remain critical at every stage, from early development through long-term maintenance, because they translate requirements into working systems and evolve them as products change.

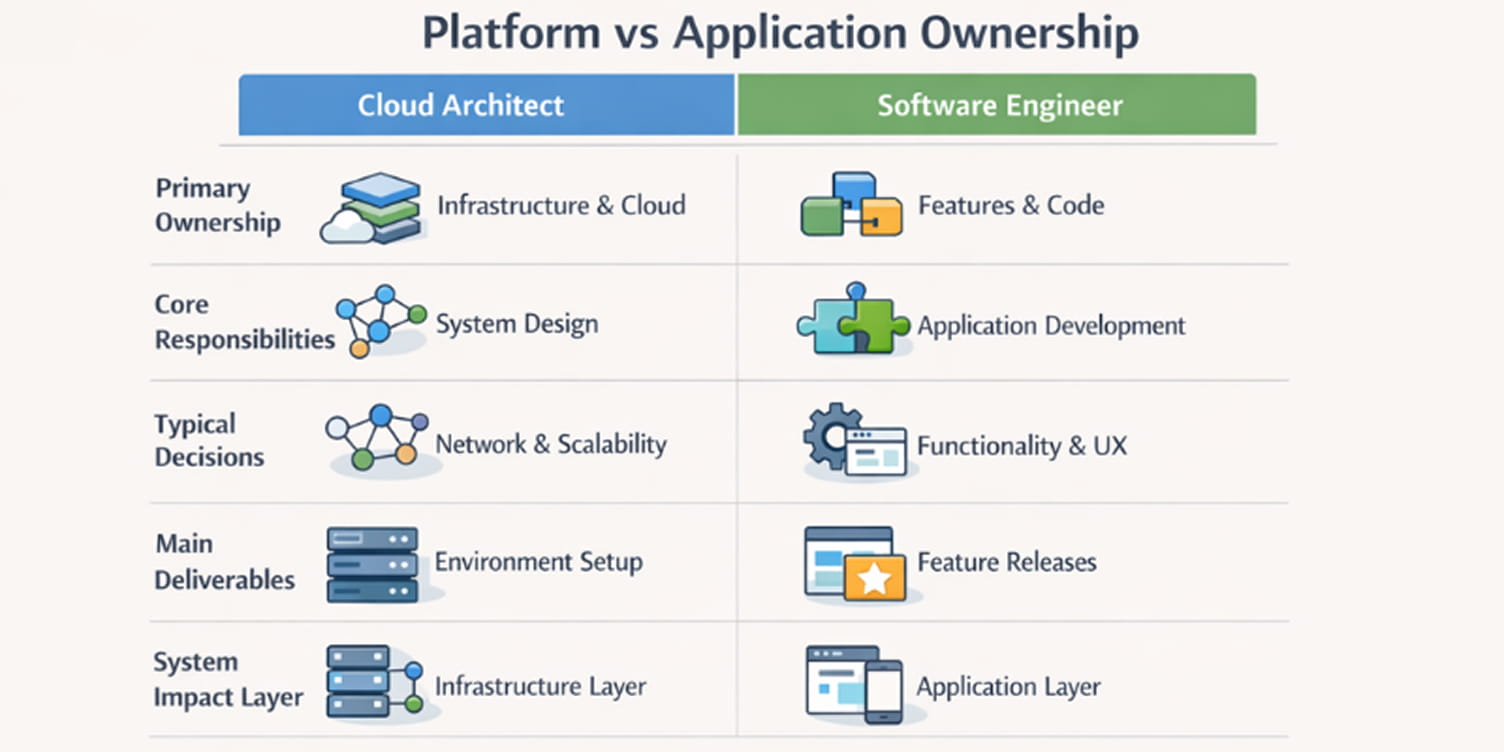

High-level role comparison table

Cloud Architect vs Software Engineer in modern software systems

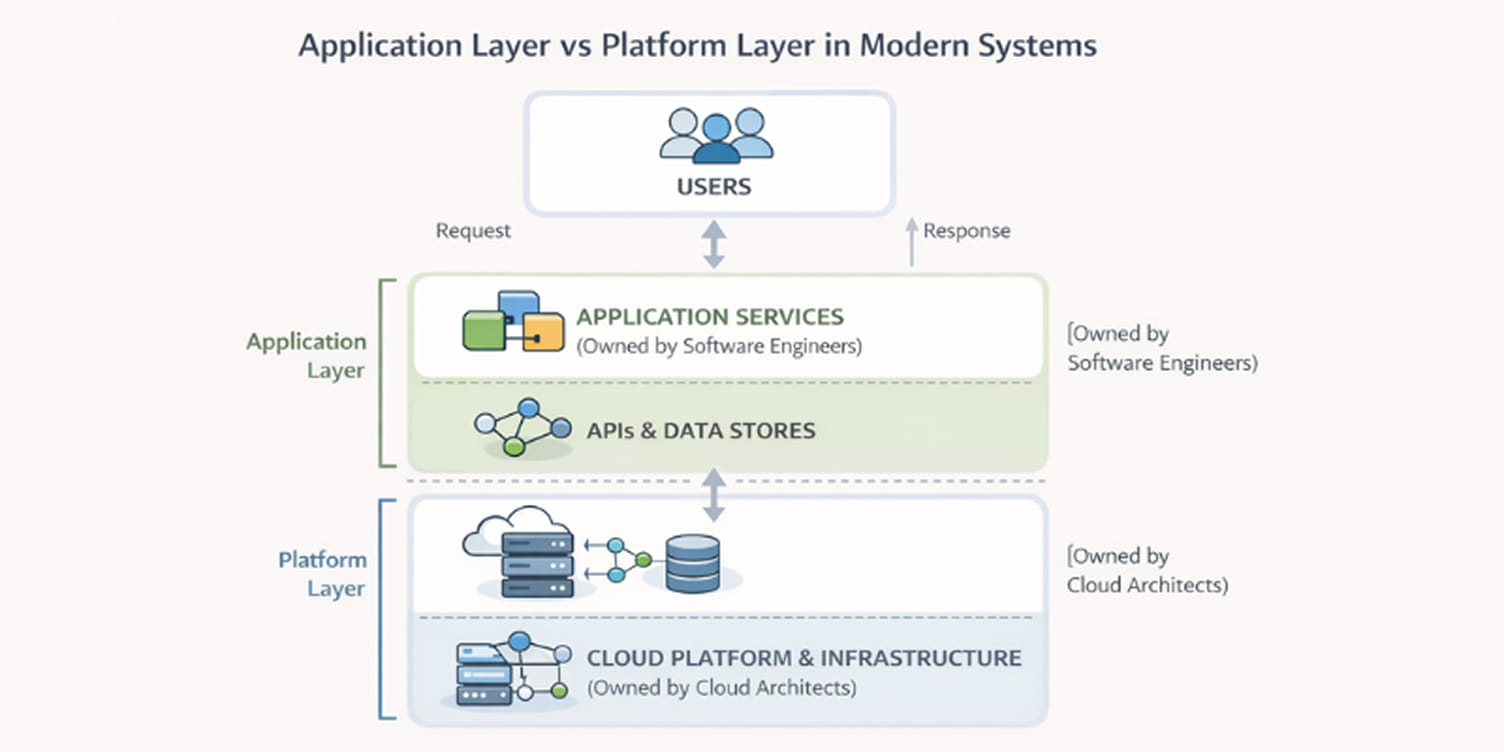

Modern software systems are built on cloud platforms, distributed services, and continuous delivery pipelines. These environments introduce design and operational decisions that go beyond writing application code.

Understanding how cloud architects and software engineers contribute at different layers helps clarify why organizations separate these roles as systems scale.

Role of cloud architects and software engineers in cloud-native applications

Software engineers define how services behave. They implement APIs, data flows, business rules, and integrations that determine what the system does.

Cloud architects define the environment those services depend on. They design how services are deployed, secured, connected, monitored, and scaled across cloud infrastructure.

Both contribute to the same product, but from different technical boundaries: one at the application layer, the other at the platform layer.

System architecture and feature development responsibilities

Cloud architects operate at the system boundary. Their responsibilities typically include:

Service and environment structure

Traffic routing and network segmentation

Failure isolation and redundancy models

Separation between development, staging, and production environments

These decisions establish the constraints within which applications must run.

Software engineers work inside those constraints. They design features, define data models, implement workflows, and optimize application behavior. Their focus is correctness, maintainability, and the safe delivery of changes.

Impact on system reliability, performance, security, and cost

Architectural decisions shape system reliability through deployment strategies, fault isolation, and recovery mechanisms. A stable platform can absorb failures without affecting users, while weak architecture can turn small defects into outages.

Performance is influenced by both roles. Cloud architects control service placement and resource allocation. Software engineers control how efficiently applications use those resources through code structure and data access patterns.

Security responsibilities are divided by layer. Architects design identity models, network boundaries, and encryption standards. Engineers implement authentication logic, authorization checks, and secure data handling within services.

Cost is primarily driven by infrastructure choices such as compute models, storage tiers, scaling policies, and regional deployments. Engineers affect cost indirectly through application efficiency and resource usage behavior.

Real-world example of a cloud architect and software engineer's responsibilities

Consider a SaaS platform composed of multiple services deployed across regions.

A cloud architect designs the deployment topology, selects managed databases, defines network boundaries, and configures monitoring and disaster recovery.

Software engineers implement the billing service, user management service, and reporting APIs that operate within that platform.

Both roles contribute to the same system, but at different layers. One defines how the system survives change and failure. The other defines what the system actually does.

Role, scope and ownership in engineering teams

In modern engineering organizations, unclear ownership leads to slow delivery, fragile systems, and operational gaps. Titles alone do not prevent this. What matters is how responsibilities are defined and enforced across teams.

Understanding where cloud architects and software engineers hold authority helps organizations design effective workflows and helps individuals evaluate where they fit.

Technical ownership of cloud architects and software engineers

Cloud architects typically own:

Infrastructure architecture and environment design

Network topology and service connectivity

Identity, access control, and platform security standards

Deployment models and disaster recovery strategy

Platform-level monitoring and reliability tooling

This ownership gives them control over how systems are structured and operated at scale, even when they are not writing application code day to day.

Software engineers typically own:

Application codebases and service logic

Data models and persistence layers

APIs and internal service contracts

Testing, debugging, and feature delivery

Ongoing maintenance and refactoring

This ownership places them closest to product behavior and user-facing functionality.

Where responsibilities of cloud architects and software engineers overlap

Not all system responsibilities fall cleanly into application or infrastructure categories. Some areas require shared ownership because failures or inefficiencies usually involve both platform design and application behavior.

Some responsibilities sit between the two roles:

Observability and logging standards

Performance tuning at both infrastructure and application layers

Security reviews and threat modeling

Incident response and post-incident analysis

In practice, cloud architects define platform capabilities and constraints, while software engineers adapt their services to operate effectively within those boundaries. Collaboration is required to avoid blind spots where issues fall between teams.

How cloud architects and software engineers fit into team structures

In product teams, software engineers work directly with product managers and designers to deliver features. Cloud architects are often consulted when changes affect deployment models, scaling behavior, or system reliability.

In platform or infrastructure teams, cloud architects usually play a central role. They design shared services, internal tooling, and standards that product teams rely on. Software engineers in these teams may focus on building platform services rather than end-user features. This is common in organizations building cloud-based platforms through dedicated cloud development solutions.

In DevOps workflows, responsibility is shared. Cloud architects define the structure of pipelines, environment separation, and access controls. Software engineers integrate testing, deployment automation, and service configuration into their development process.

In large organizations, these roles are often formalized into separate teams. In smaller organizations, they may be combined in the same individuals, but the ownership areas remain distinct even when the titles do not.

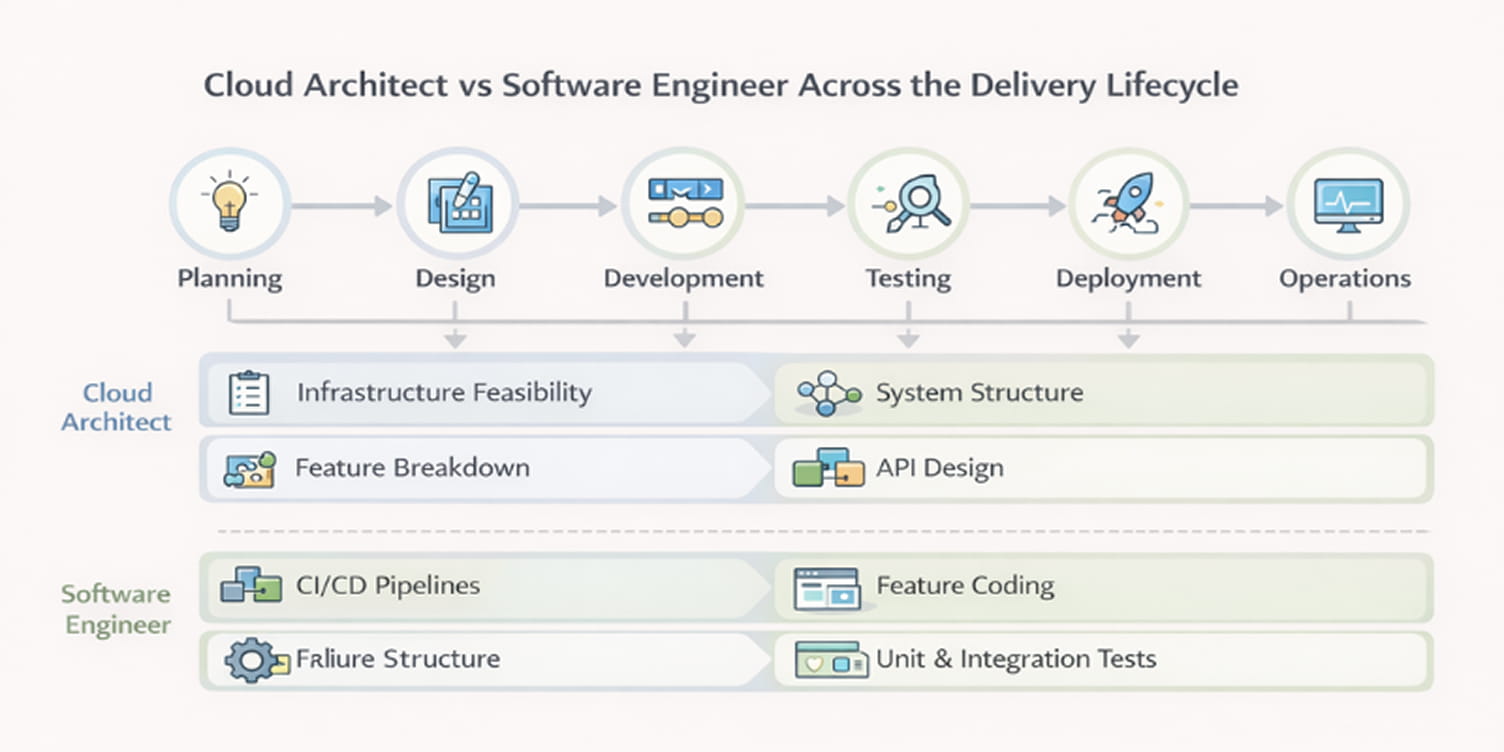

Cloud architect and software engineer across the software delivery lifecycle

The difference between cloud architects and software engineers becomes clearer when viewed through the software delivery lifecycle. Each stage introduces technical decisions that affect system stability, development velocity, and operational risk. Understanding who leads which decisions helps teams coordinate effectively and helps individuals evaluate where their work will be concentrated.

Planning and technical feasibility assessment

Cloud architects evaluate platform-level feasibility before development begins. This includes assessing whether existing infrastructure can support proposed features and what changes may be required to meet platform-level constraints targets.

Their planning considerations often include:

Expected traffic growth and usage patterns

Availability and recovery objectives

Regulatory and data residency constraints

Cost boundaries for compute, storage, and networking

Software engineers translate product requirements into concrete technical work. They break features into deliverable components, identify dependencies between services, and surface implementation risks that could affect timelines or system behavior.

System and Architecture Design

Cloud architects design the system structure that applications will run within. This typically covers:

Service boundaries and communication patterns

Network layout and environment separation

Identity and access control models

Data placement and replication strategy

Software engineers design how features operate inside that structure. They define APIs, request flows, data schemas, and failure-handling logic to ensure services behave predictably under normal and degraded conditions.

Application and Interface Design

Software engineers focus on designing application behavior that users and other systems interact with directly. This includes:

API contracts and request validation rules

User-facing workflows and error handling

Data transformation and consistency guarantees

Cloud architects review these designs to ensure they align with platform constraints such as network policies, identity models, and service isolation requirements.

Feature Development and Integration

Software engineers lead day-to-day implementation work. They write and review application code, integrate internal services and external systems, and maintain automated tests to ensure changes do not introduce regressions. Over time, they also refactor code to control complexity and reduce technical debt.

This stage is where product requirements are translated into working functionality. Decisions made here directly affect application stability and long-term maintainability

Cloud architects support development by validating infrastructure assumptions, updating platform standards when required, and resolving environment-level blockers such as network configuration, access permissions, or deployment tooling limitations.

Validation and Quality Assurance Testing

Software engineers focus on validating application behavior through:

Unit tests for individual components

Integration tests across services

Contract tests for API compatibility

Cloud architects ensure that testing environments reflect production conditions closely enough to reveal systemic issues. This may involve configuring realistic network boundaries, simulating partial failures, or validating how services behave under load.

Release Management and Deployment

Cloud architects design how changes move safely into production. They define rollout strategies, failure containment mechanisms, and environment promotion workflows that reduce risk when new versions are introduced.

Their decisions determine how quickly issues can be detected and reversed and how much impact a faulty release can have on users or dependent systems. This layer of control is especially important in distributed systems where failures can propagate quickly.

Software engineers prepare releases by packaging services, setting runtime configuration, and verifying that new features behave correctly within the defined deployment model before and after production rollout.

Production Operations and System Maintenance

Cloud architects focus on long-term platform health. Their responsibilities include capacity planning, infrastructure upgrades, reliability improvements, and maintaining observability standards across environments.

Software engineers monitor service-level metrics, respond to application incidents, analyze production errors, and optimize performance based on real usage data.

Structured comparison by lifecycle stage table

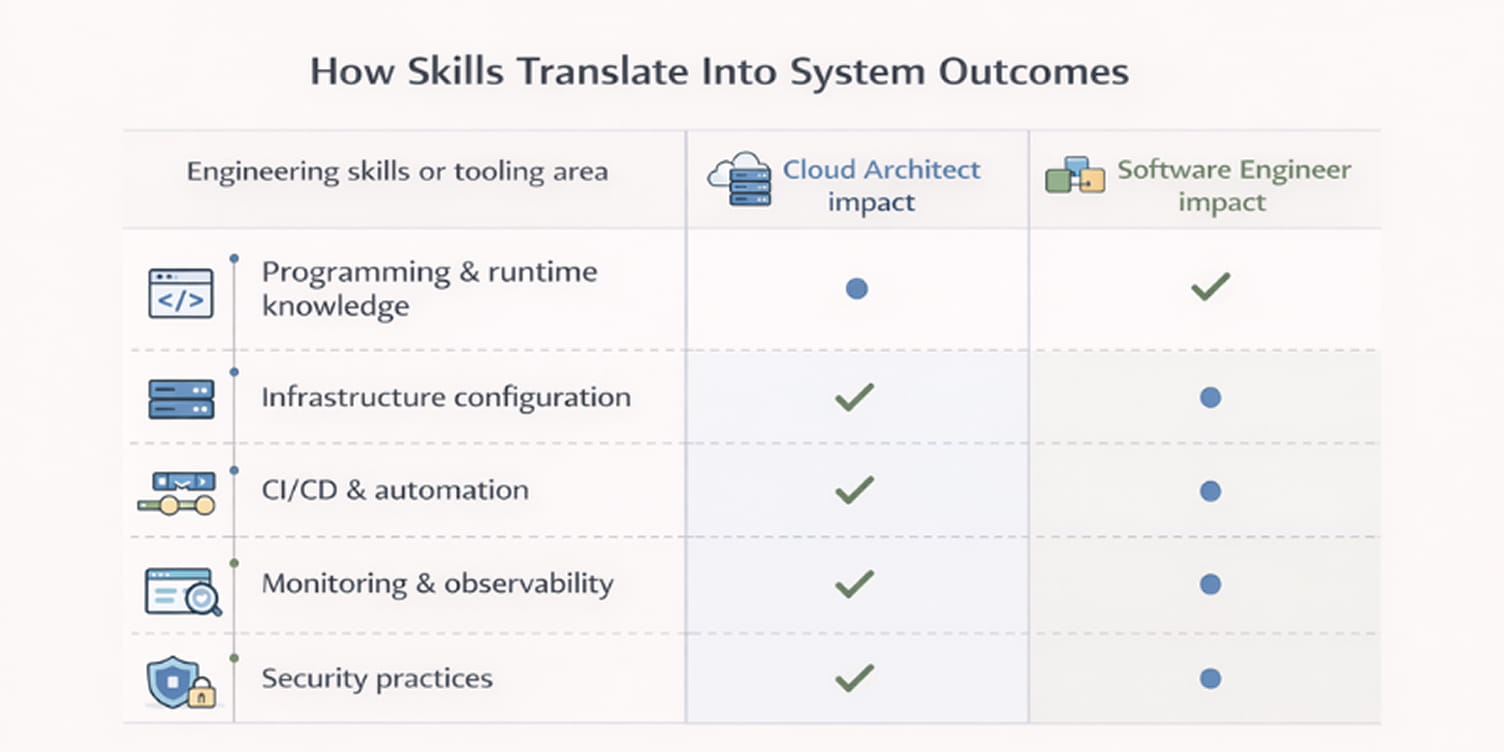

Skills and tooling that drive engineering outcomes

Job descriptions often list long sets of technologies, but in practice what matters is how those skills affect system behavior and business results. Cloud architects and software engineers invest in different technical areas because they are accountable for different outcomes, such as delivery speed and overall production behavior.

Programming focus versus infrastructure focus

Software engineers concentrate on application-level skills:

Programming languages and runtime behavior

API design and data modeling

Testing strategies and debugging

Code maintainability and refactoring

These skills directly influence feature correctness, response times, and how safely new functionality can be released.

Cloud architects focus on platform-level skills:

Cloud service configuration and resource modeling

Network design and traffic control

Identity and access management

Deployment architecture and failure modeling

These skills determine whether systems scale predictably, recover from outages, and comply with security and regulatory requirements.

Tooling categories and what they influence

Different tool categories exist because they optimize different system outcomes.

Application development tools

Used mainly by software engineers. This includes languages, frameworks, ORMs, testing libraries, and package managers. Proficiency here reduces defect rates and shortens release cycles.

Infrastructure and platform tools

Used mainly by cloud architects. This includes cloud platforms such as AWS, Azure, and Google Cloud, infrastructure-as-code tools, container orchestration systems, and network configuration tooling. These determine environment consistency, fault tolerance, and operational overhead.

CI/CD and observability tools

Shared across both roles. Build pipelines, deployment automation, monitoring systems, and logging platforms shape how quickly teams detect issues and how safely they deploy changes.

Teams typically standardize on a small, well-defined set of build, monitoring, and deployment platforms, forming standardized DevOps toolchains across engineering teams.

How tools translate into real engineering outcomes

The practical difference between these toolsets becomes clear when mapped to measurable outcomes.

Tools emphasized by software engineers tend to improve:

Feature delivery speed

Application correctness and data integrity

API stability and backward compatibility

Long-term codebase maintainability

Tools emphasized by cloud architects tend to improve:

System availability and fault tolerance

Performance consistency under load

Platform security boundaries

Infrastructure efficiency

Shared tooling such as CI/CD platforms and monitoring systems affects cross-team outcomes, including incident response time, release confidence, and long-term operational stability.

Collaboration model between cloud architects and software engineers

Most production systems fail or succeed not because of individual technical skill, but because of how well platform and application work are coordinated. Cloud architects and software engineers operate at different layers, but their decisions intersect constantly during design, delivery, and operations. Understanding how this collaboration works in practice is important when evaluating either role.

Typical cloud architect and software engineer workflow

In many organizations, collaboration follows a predictable pattern across feature development and system changes:

Cloud Architects define platform constraints, deployment models, and security boundaries

Software Engineers design and implement services within those constraints

Both review changes that affect reliability, scaling behavior, or data exposure

Platform updates and application changes are coordinated through shared release cycles

This workflow reduces the risk of application changes violating infrastructure assumptions or platform changes breaking service behavior.

For example, when a team introduces a new authentication service, cloud architects typically review identity integration, network exposure, and secret management, while software engineers implement token handling, request validation, and service-to-service authorization.

Releasing the feature requires coordination on both the platform configuration and application logic to avoid breaking existing clients.

Technical decision ownership by role

Ownership is usually split by layer.

Cloud architects typically own decisions related to infrastructure architecture, service topology, identity models, network segmentation, and deployment strategy.

Software engineers typically own decisions related to application logic, data modeling, API contracts, error handling, and performance optimization within services.

Some decisions require joint review, especially when changes affect system reliability, regulatory compliance, or long-term operational cost.

This shared ownership model reflects how modern DevOps practices distribute responsibility across platform and application teams.

Handoffs and feedback loops between teams

Handoffs occur whenever responsibility moves between platform and application layers. Examples include new service onboarding, changes to deployment pipelines, and updates to security or networking policies.

Effective teams establish feedback loops through:

Architecture and design reviews

Shared technical documentation and platform standards

Incident postmortems and reliability reviews

Monitoring dashboards visible to both roles

These mechanisms allow application teams to surface platform limitations early and platform teams to detect recurring application-level risks.

Collaboration during incidents and escalations

During production incidents, collaboration becomes more structured.

Cloud architects usually focus on platform stability, traffic routing, infrastructure failures, and capacity constraints. Software engineers investigate service behavior, recent code changes, data consistency issues, and API failures.

Clear escalation paths and predefined ownership reduce response time and prevent duplicated effort. Teams that practice joint incident reviews tend to improve both platform design and application reliability over time.

Common collaboration challenges

Even in mature organizations, several issues appear regularly:

Platform standards that slow down feature delivery

Application designs that conflict with infrastructure constraints

Unclear ownership during incidents

Delayed feedback between platform and product teams

Incomplete or outdated technical documentation

In more complex environments, organizations sometimes work with specialized DevOps consulting firms to formalize processes and reduce coordination overhead between platform and product teams.

These challenges are usually organizational rather than technical, but they strongly influence system reliability, release confidence, and team productivity.

Career progression for cloud architects and software engineers

Role titles describe current responsibilities, but career progression in software organizations is shaped by how technical scope, system ownership, and decision authority expand over time.

For engineers choosing between cloud architecture and software engineering paths, understanding how each role evolves helps set realistic expectations about long-term work, influence, and daily responsibilities.

Career progression from entry-level to senior roles

Software engineers typically begin with narrow ownership over specific services or features. Early responsibilities focus on writing code, fixing defects, and learning internal systems. As experience grows, engineers take on larger components, design complex workflows, review others’ code, and influence architectural decisions within their teams.

Cloud architects usually move into the role after experience in software engineering, infrastructure, or DevOps. Early architectural responsibilities often involve designing parts of the platform or supporting specific systems. With seniority, scope expands to include organization-wide platform standards, long-term infrastructure planning, and cross-team technical alignment.

Individual contributor and leadership career paths

Both roles support advancement without moving into people management.

Senior software engineers can progress to staff or principal roles where they lead technical direction across multiple teams, define engineering standards, and mentor others while remaining hands-on.

Cloud architects follow a similar path, progressing to lead architect or platform architect roles with responsibility for enterprise-scale systems and technical governance.

Leadership paths also exist. Engineers may move into engineering management or platform leadership roles, trading direct technical ownership for responsibility over team performance, delivery outcomes, and system reliability at an organizational level.

Transition paths between software engineering and cloud architecture

Transitions between roles are common. Software engineers often move toward cloud architecture after gaining experience in distributed systems, operations, or platform engineering. Conversely, cloud architects may return to application-focused roles when organizations need deep system knowledge within product teams.

As responsibility increases, daily work shifts:

From implementing features to reviewing designs and tradeoffs

From solving isolated problems to managing system-wide dependencies

From short-term delivery goals to long-term platform stability

These changes affect how much time is spent coding, designing, coordinating, and reviewing, which is an important consideration when choosing a long-term path.

How career progression differs by organization type

Career progression is also shaped by the size and maturity of the company.

In smaller organizations, software engineers and cloud architects often wear multiple hats. Engineers may handle infrastructure decisions, and architects may contribute directly to application code. Progression tends to increase responsibility breadth more than specialization.

In larger organizations, roles become more specialized. Software engineers deepen expertise in specific domains or systems, while cloud architects focus on platform strategy, cross-team standards, and long-term infrastructure evolution. Advancement is measured more by technical influence and system impact than by title changes alone.

How technical influence grows over time

Beyond formal titles, progression is reflected in:

The size and criticality of systems owned

The number of teams affected by technical decisions

Involvement in architectural reviews and long-term planning

Responsibility during major incidents or system migrations

For both roles, seniority is less about seniority labels and more about how much of the system’s long-term health depends on their decisions.

Compensation and market demand for cloud architects and software engineers

Compensation and job demand are practical factors in any role-level decision. For engineering professionals choosing between cloud architecture and software engineering paths, data-driven context helps set realistic expectations about earnings, hiring trends, and where opportunities are concentrated in today’s market.

Current salary ranges in the US market

In the United States, compensation reflects responsibility scope and market demand for advanced technical skills.

Cloud architects typically command higher averages due to platform-level ownership and cross-team influence. Reports indicate average U.S. salaries around $143,000 to $158,000 per year for cloud architects based on aggregated data from cloud salary benchmarks.

Software engineers also earn competitive salaries across experience levels, with many mid-career positions falling in the $107,000 to $138,000 range, according to recent IT market salary data.

Both roles tend to outpace median wages across other occupations due to sustained demand for cloud-capable and application-development expertise.

Job demand and growth projections

Demand for related roles remains strong.

Employment of network and computer systems architects, a category that includes cloud-oriented roles, is projected to grow about 12 percent from 2024 to 2034, faster than the average for all occupations.

Broader computer and information technology occupations are also expected to grow faster than average, driven by ongoing digital transformation across industries.

These trends reflect sustained investment in cloud infrastructure, distributed systems, and software products that require both application and platform engineering expertise.

Hiring patterns and employer expectations

Although job titles vary across organizations, hiring criteria tend to follow consistent patterns for each role.

Software engineer positions commonly emphasize strong programming fundamentals, experience with distributed systems, practical use of CI/CD pipelines, and familiarity with integrating cloud services into application workflows.

Cloud architect roles typically prioritize experience with multi-environment deployments, platform and infrastructure design, security architecture, scalability planning, and long-term operational reliability.

Across both paths, specialized expertise in areas such as site reliability engineering, cloud security, and cross-system integration can increase compensation potential and expand job opportunities, particularly in organizations operating complex or regulated platforms.

Cloud architect and software engineer salary comparison

(Data sources include U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics and aggregated salary reporting.)

This overview offers grounded insight into how compensation and market demand differ across these two career paths, helping you weigh expected earnings alongside responsibilities and long-term career direction.

How to choose between cloud architect and software engineer roles

Both cloud architects and software engineers build critical parts of modern systems, but the day-to-day work, problem types, and long-term focus differ. Choosing between them is less about prestige and more about how your background, interests, and working style align with the responsibilities each role carries.

Decision criteria by engineering background

Your current experience often points naturally toward one path.

Engineers with strong application development backgrounds tend to adapt well to software engineering roles. This includes experience with backend or frontend development, API design, data modeling, and feature delivery within product teams.

Engineers with experience in infrastructure, DevOps, networking, or system administration often transition more smoothly into cloud architecture roles, where platform design, environment management, and reliability engineering are central.

Those with mixed experience across development and operations may find either path viable, depending on which layer of the system they prefer to own long-term.

Work-style preferences

The two roles reward different working styles.

Software engineers typically spend more time:

Writing and reviewing code

Iterating on features

Debugging application behavior

Collaborating closely with product and design teams

Cloud architects typically spend more time:

Designing systems and infrastructure models

Reviewing architectural changes

Analyzing reliability and security risks

Coordinating across multiple engineering teams

If you prefer deep focus on implementation and rapid iteration, software engineering often fits better. If you prefer systems thinking and long-range technical planning, cloud architecture may be a stronger match.

Technical interests

Interest in specific technical problems is another useful signal.

Software engineers tend to be drawn to application performance, data consistency, API design, user behavior, and development tooling.

Cloud architects tend to focus on distributed systems behavior, fault tolerance, security boundaries, deployment strategies, and cost optimization.

Sustained interest in these problem areas matters more than short-term salary differences, as it shapes what you will be working on daily for years.

Long-term goals

Long-term career direction also differs.

Software engineering paths often lead toward staff or principal engineer roles focused on complex systems, product architecture, or domain expertise.

Cloud architecture paths often lead toward platform leadership, enterprise architecture, or organization-wide infrastructure strategy roles.

Both can transition into engineering management, but the technical lens you develop will differ based on the systems you spend the most time designing and maintaining.

Simple decision checklist

Use the following as a quick self-assessment:

Do I prefer building features or designing systems?

Do I enjoy debugging application logic or analyzing infrastructure behavior?

Do I want to work mainly within one product or across many teams and services?

Do I find deployment models and reliability planning more interesting than UI and API design?

Do I want my long-term influence to be product-centric or platform-centric?

Clear answers to these questions usually point toward one role more strongly than the other.

Common misunderstandings in cloud and software engineering roles

Confusion around cloud and software roles is common in hiring and team design. Inaccurate titles, blurred ownership, and unrealistic expectations often lead to delivery delays, fragile systems, and frustrated engineers. Understanding these patterns helps individuals evaluate roles more accurately and helps organizations structure teams more effectively.

Misuse of job titles

Many companies use Cloud Architect, Cloud Engineer, and DevOps Engineer interchangeably, even though the responsibilities differ significantly. In some organizations, a Cloud Architect title is assigned to hands-on infrastructure operators. In others, it refers to a system-level designer with little day-to-day operational work.

Similarly, software engineers can range from feature-focused application developers to engineers responsible for internal platforms or distributed systems. Titles alone rarely reflect actual scope, so role descriptions and ownership boundaries matter more than labels.

Overlapping responsibilities

Some overlap between roles is unavoidable, especially in smaller teams. Problems arise when overlap is unplanned.

Without clear boundaries:

Platform work may be treated as application work

Infrastructure decisions may be deferred until late in development

Reliability tasks may fall between teams

Well-functioning organizations explicitly define who owns platform design, who owns application behavior, and where collaboration is required, rather than assuming responsibilities will sort themselves out.

Unrealistic expectations

A common hiring mistake is expecting one role to fully cover both system architecture and complex application development.

Cloud architects are sometimes expected to design platforms, manage infrastructure, handle security, and write production application code simultaneously. Software engineers are sometimes expected to build features while also designing deployment systems and managing cloud environments.

These expectations are difficult to sustain at scale and often lead to burnout or shallow expertise in both areas.

Organizational design pitfalls

Team structure can amplify or reduce these issues.

Centralized platform teams with no connection to product teams can become bottlenecks. Fully decentralized teams with no architectural ownership can drift into inconsistent infrastructure and security practices.

Other common pitfalls include:

No formal ownership of reliability and cost management

Architectural decisions made without application context

Application teams blocked by undocumented platform constraints

Incident response roles that are unclear during failures

Organizations that align roles with actual system ownership tend to deliver more reliably and retain senior engineers longer.

Conclusion

Cloud architects and software engineers solve different classes of problems inside modern systems. One role focuses on how software operates at scale, under failure, and within constraints. The other focuses on how software behaves, evolves, and delivers value to users. Both are essential, but they create impact at different layers of the stack.

Cloud architecture delivers the most value when systems become distributed, regulated, cost-sensitive, or reliability-critical. Software engineering delivers the most value when products must move quickly, integrate cleanly, and remain maintainable as features and usage grow. Neither role replaces the other; they compound each other’s effectiveness when ownership is clear.

Choosing between them comes down to where you want your technical influence to sit long-term: inside the application or across the platform it runs on. That decision shapes not just daily work but also the type of problems you will spend years solving.