Cloud Application Development: Process, Costs, and Risks

Cloud application development has shifted from a niche engineering approach to the default way modern software is built. Companies no longer design applications around fixed servers or static infrastructure. When these realities are ignored, teams often face cost overruns, fragile systems, and security gaps.

Gartner forecasts that worldwide public cloud spending will reach $723.4 billion in 2025, up from $595.7 billion in 2024, showing how central cloud platforms have become to business-critical software.

This guide explains how cloud application development works in practice. You will learn about application types and architectures, the development lifecycle, technology stacks, cost drivers, security responsibilities, common risks, real-world use cases, and how to decide when cloud is the right technical choice.

What cloud application development means in practice

Teams usually reach this topic when traditional infrastructure starts slowing delivery or increasing risk. Deployments become harder to manage, costs are unpredictable, and scaling the application means rethinking servers, security, and operations every time demand changes.

Cloud application development addresses these problems by changing how software is designed, deployed, and operated from the start. It is not just about hosting code on cloud servers. It is about building applications that assume distributed systems, automation, and continuous change as normal conditions.

What cloud application development is

Cloud application development is the practice of building software that relies on cloud platforms for its core infrastructure and services. Instead of managing physical servers, teams use managed compute, storage, networking, identity, and monitoring services provided by cloud providers.

In real projects, this changes how applications are built and operated:

Infrastructure is created and updated through code instead of manual setup

Deployments are automated and repeatable

Failures are expected and designed around

Capacity can change without redesigning the system

The result is software that can be updated frequently, operated with smaller teams, and adapted as usage patterns evolve.

Cloud-native applications vs cloud-hosted applications

Not every application running in the cloud is built the same way.

Cloud-native applications are designed specifically for cloud environments. They use managed services such as cloud databases, identity systems, and messaging platforms, and often follow architectures like microservices or serverless. These systems treat infrastructure as temporary and focus on resilience and automation.

Cloud-hosted applications are traditional systems that were originally built for on-premise servers and later moved to cloud virtual machines. They run in the cloud, but their architecture and operational model remain largely unchanged.

This difference matters because cloud-native systems usually achieve better cost control, reliability, and operational flexibility over time.

What qualifies an application as cloud-based

In practice, an application is considered cloud-based when most of the following are true:

Infrastructure is provisioned through cloud platforms

Core services such as databases and authentication come from cloud providers

Deployment and updates are automated

The system runs across multiple servers or regions

Monitoring and logging are built into daily operations

If these elements are missing, the application may be hosted in the cloud but not truly designed for it.

Who typically uses this approach

Cloud application development is commonly used by:

SaaS companies delivering subscription software

Enterprises modernizing internal systems

Startups building new digital products

Organizations serving users across multiple regions

For decision-makers, the key point is that this approach changes long-term operating costs, security responsibilities, and how quickly software can evolve. It is an architectural commitment, not just a hosting decision.

Many organizations formalize this shift by working with cloud development solutions that standardize architecture, security controls, and deployment workflows.

How cloud applications differ from traditional applications

This comparison matters because it directly affects system design, operating costs, release speed, and long-term maintenance effort. Teams evaluating cloud adoption often focus on infrastructure first, but the real differences show up in how software is built, deployed, and supported over time.

The contrast becomes easier to evaluate when the two approaches are compared across core technical and operational areas.

This distinction affects not only how systems are built but also how teams budget, staff, and manage software over time.

Architecture and system design

Traditional applications are commonly built as tightly coupled systems that run on a fixed group of servers. Capacity planning happens upfront, and scaling usually requires adding hardware or redesigning parts of the application.

Cloud applications are designed to run across distributed services. Components can be deployed independently, capacity can adjust based on demand, and failures are isolated rather than system-wide. This changes how teams approach reliability and growth from the beginning.

Deployment model

Deployment processes differ in predictable ways:

Traditional systems rely on scheduled releases and manual steps

Downtime windows are common

Rollbacks can be slow and risky

Cloud deployments are usually automated through pipelines. New versions can be released in small increments, tested in parallel environments, and rolled back quickly if issues appear, reducing operational risk.

Maintenance and updates

In traditional environments, teams manage operating systems, security patches, hardware failures, and capacity upgrades in addition to application code. Infrastructure maintenance competes directly with feature development for time and budget.

In cloud environments, many infrastructure tasks shift to the platform provider. Teams still manage application behavior and configuration, but routine system upkeep becomes less of a bottleneck.

Cost structure and infrastructure ownership

The financial model differs in clear ways:

Traditional applications require upfront investment in servers and data centers

Cloud applications use usage-based pricing for compute, storage, and network traffic

Infrastructure assets are owned in traditional setups and rented in cloud environments

This shifts spending from fixed capital costs to variable operating costs and changes how organizations plan budgets, staffing, and long-term system growth.

Types of cloud applications and deployment models

Choosing the right cloud model affects how much control teams retain, how systems are built, and how predictable long-term costs will be. Many projects run into avoidable issues because the service type or deployment setup is selected without understanding these trade-offs.

Cloud service models

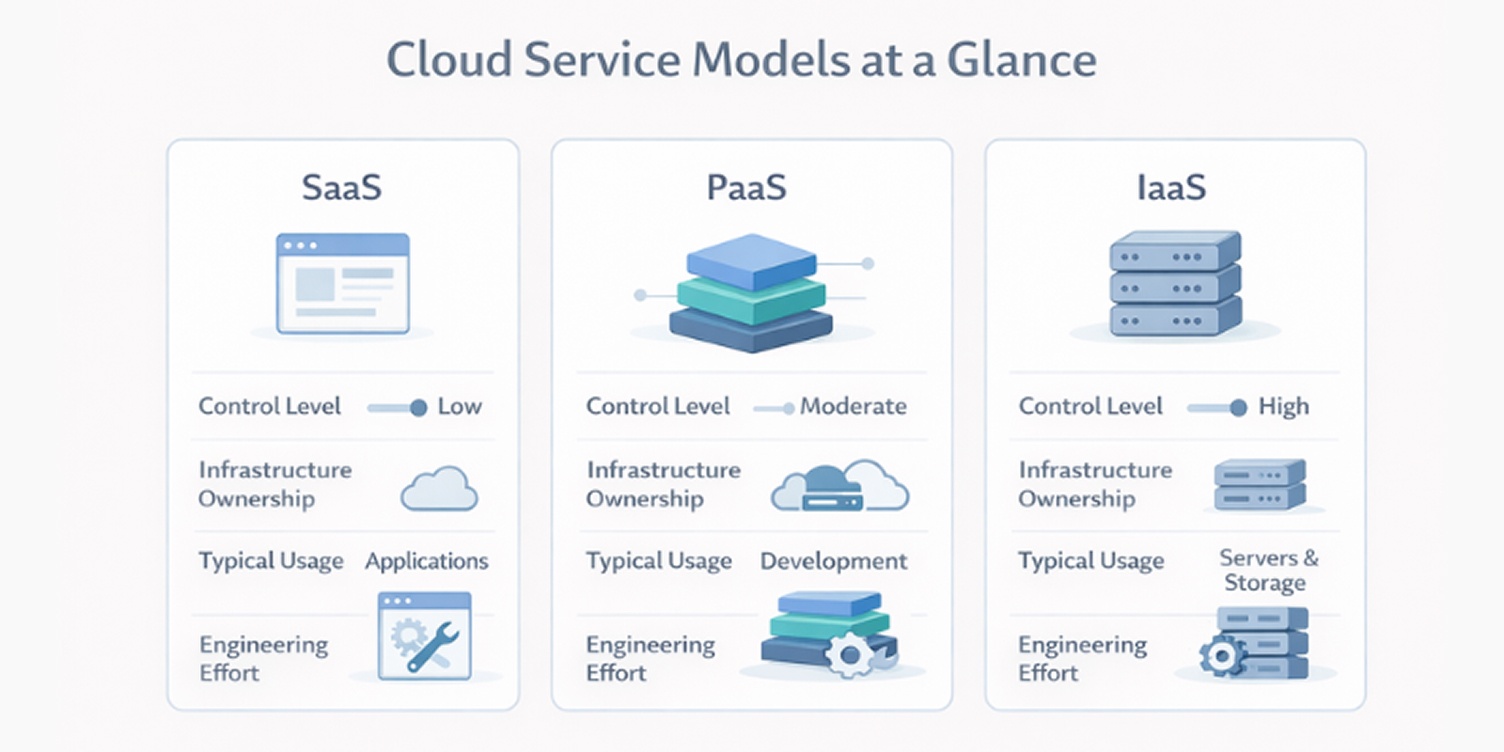

Cloud platforms are commonly grouped into three service types:

Software as a Service (SaaS): fully managed applications delivered over the internet

Platform as a Service (PaaS): development platforms that manage infrastructure and runtime

Infrastructure as a Service (IaaS): virtualized servers, storage, and networking resources

Each model represents a different balance between convenience and control.

The differences between these models become clearer when viewed in terms of control, responsibility, and operational effort.

Most teams combine these models in practice, using SaaS for standard business functions, PaaS for new development, and IaaS where deeper system control is required.

SaaS is used when organizations want to use software without managing updates, servers, or security patches. Common examples include CRM systems, accounting tools, and collaboration platforms. The provider handles both the application and the infrastructure.

PaaS is chosen when teams are building their own applications but do not want to manage operating systems or server configuration. Developers deploy code while the platform manages scaling, runtime environments, and system updates.

IaaS is used when teams need full control over the operating environment. It replaces physical data centers with virtual infrastructure but leaves responsibility for system configuration, security, and maintenance with the organization.

Cloud deployment models

Deployment models describe where workloads run and who controls the infrastructure:

Public cloud: shared infrastructure operated by a provider

Private cloud: infrastructure dedicated to one organization

Hybrid cloud: a combination of public and private environments

Public cloud environments are common for new applications that require fast provisioning. Private clouds are often selected for regulatory or data-sensitivity reasons. Hybrid setups are used when some systems must remain isolated while others benefit from public cloud services.

When each model makes sense

Most organizations use more than one model. The right mix depends on practical constraints rather than technology preference.

Key factors typically include:

Required level of infrastructure control

Data protection and compliance obligations

Expected traffic variability

Internal operations and support capacity

The goal is to balance operational effort, risk exposure, and long-term cost rather than standardizing on a single cloud approach.

Common architecture patterns used in cloud applications

Architecture decisions shape how an application scales, how resilient it is to failures, and how complex it becomes to operate over time. In cloud environments, these choices also affect cost behavior and how quickly teams can ship changes.

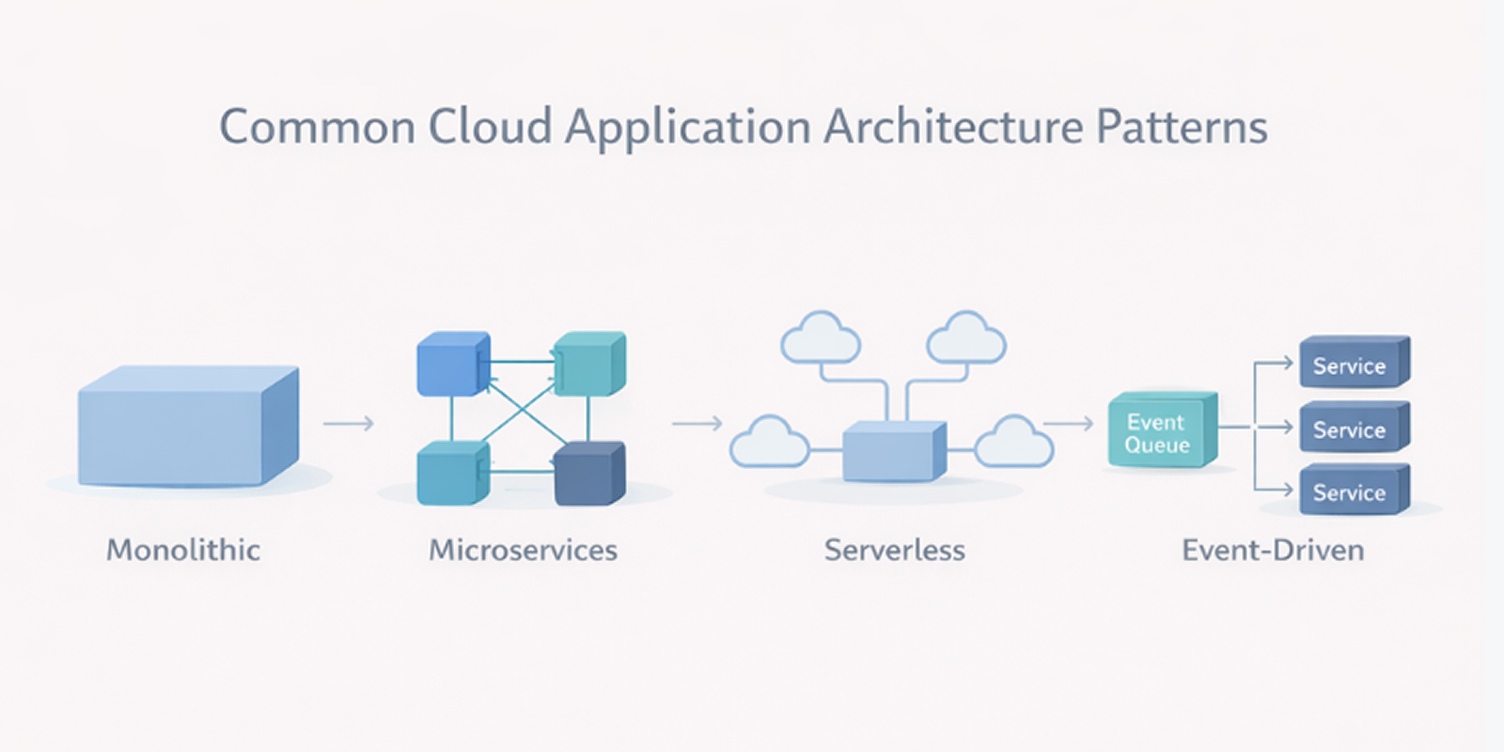

Monolithic and microservices architectures

Most teams start by choosing between these two structural approaches.

Monolithic applications package most functionality into a single system that is built and deployed as one unit. This keeps early development simple but makes it harder to scale or change individual features without affecting the whole application.

Microservices architectures divide the system into smaller services that communicate over APIs. Each service can be deployed independently, which improves flexibility and fault isolation but increases coordination, monitoring, and operational overhead.

For example, a simple internal reporting tool often starts as a monolith, while a large e-commerce platform typically splits checkout, payments, catalog, and search into separate microservices.

Key differences teams usually evaluate:

Deployment model: single unit vs independent services

Scaling approach: entire system vs individual components

Failure impact: system-wide vs isolated

Operational complexity: lower vs higher

Serverless architecture

Serverless systems run application logic as short-lived functions managed by the cloud provider. Teams do not manage servers, operating systems, or runtime environments directly.

This approach works well for workloads with irregular traffic or background processing needs. It reduces infrastructure management effort but introduces execution limits, more complex testing workflows, and stronger dependence on provider-specific services.

Event-driven systems

Event-driven architectures trigger actions based on events such as data changes, messages, or user activity instead of fixed request–response flows.

They are commonly used for workflows that span multiple systems, such as data pipelines, billing processes, and notifications. While they improve decoupling, they also make debugging more difficult because behavior is spread across asynchronous steps.

Container-based deployments

Containers package applications and dependencies into standardized units that run consistently across environments.

Teams often adopt containers to:

Keep development and production environments consistent

Isolate services

Support horizontal scaling

Improve deployment repeatability

This approach improves portability and control but adds orchestration, networking, and service discovery complexity.

Many teams adopt this model to standardize environments and reduce deployment errors, which are core benefits of containerization in cloud systems.

The cloud application development lifecycle

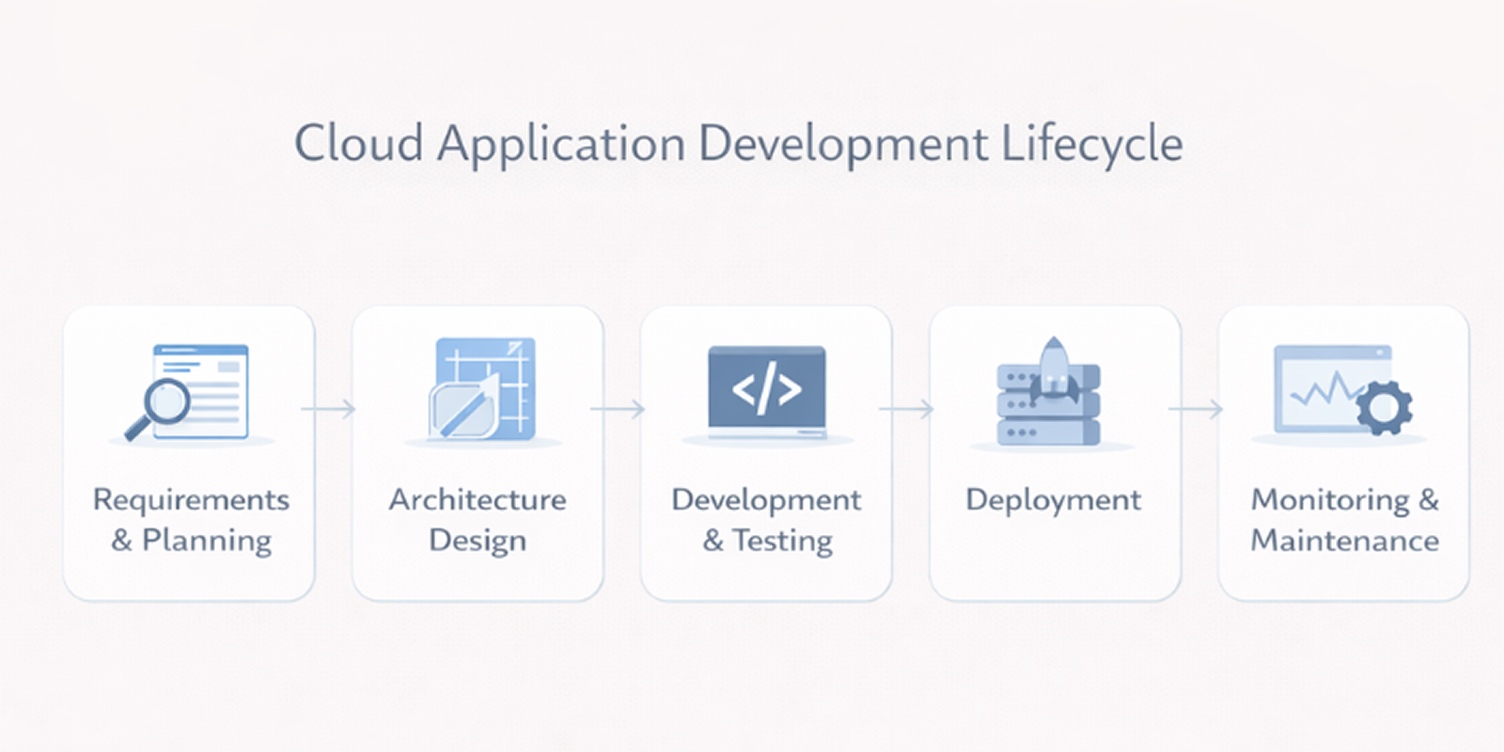

Cloud projects often fail not because of poor code, but because early technical and operational decisions are not carried through into deployment and long-term operations. A structured lifecycle helps teams manage risk, control costs, and avoid design choices that become expensive to fix later.

Requirements and planning

This phase defines what the application must do and the constraints it must operate under. Teams document user needs, data sensitivity, regulatory obligations, expected traffic levels, and how the system will integrate with existing tools.

These decisions influence architecture, security controls, and infrastructure costs. Weak planning often leads to redesigns after development has already started.

Architecture design

Architecture design translates requirements into technical structure and service boundaries.

Teams typically define:

How the application is split into services or components

Data storage and access patterns

Authentication and authorization approach

Network boundaries and failure isolation strategy

Use of managed cloud services

This stage determines how resilient, maintainable, and expensive the system will be to operate over time.

Development and testing

Development focuses on building application features, APIs, and integrations. Testing runs alongside development to validate functionality, security, and performance.

In cloud environments, automated testing pipelines are commonly used to detect regressions early and ensure that changes can be released without disrupting active users.

Deployment

Deployment moves the application into production environments in a controlled and repeatable way.

Cloud teams usually define:

Automated release pipelines

Environment configuration standards

Rollback procedures

Gradual rollout strategies

This reduces downtime risk and limits the impact of faulty releases.

These workflows are often built and maintained by DevOps development teams responsible for automation, monitoring, and release governance.

These pipelines are typically supported by a combination of CI systems, configuration managers, and DevOps automation tools that handle build execution, environment provisioning, and controlled releases.

Monitoring and long-term maintenance

Once the application is live, operational work becomes continuous. Teams monitor performance, availability, error rates, and infrastructure usage to detect problems early.

Long-term maintenance includes security patching, cost reviews, capacity adjustments, dependency upgrades, and architectural refinements as usage patterns change.

The typical technology stack for cloud application development

A cloud application is built from multiple layers, each responsible for a different part of how the system behaves, scales, and is maintained. Understanding these layers helps teams estimate effort, choose tools that fit their constraints, and avoid mismatches between application design and operational requirements.

Frontend frameworks

The frontend handles how users interact with the application through browsers or mobile devices. Most cloud applications rely on JavaScript-based frameworks that support modular interfaces and frequent updates.

Common choices include React, Angular, and Vue for web applications, along with mobile frameworks such as React Native or Flutter when the same backend serves multiple client platforms.

Backend technologies

The backend implements business logic, data processing, and integration with external systems. Cloud applications often use languages and frameworks that support concurrency, API-first design, and background processing.

Typical options include Node.js, Java with Spring Boot, Python with Django or FastAPI, and Go-based services. The choice usually depends on existing team expertise, performance needs, and the surrounding cloud ecosystem.

Cloud service layers

Cloud applications rarely manage infrastructure components directly. Instead, they rely on managed services provided by cloud platforms to handle common system functions that would otherwise require dedicated operational work.

These services commonly include:

Compute services for running application code

Identity and access management systems

Messaging and queuing services

Load balancing and traffic routing

Secrets and configuration management

Using managed services reduces operational burden and shortens setup time, but it also increases dependence on specific cloud platforms and their service limits.

Databases and storage

Cloud environments separate transactional data from file and object storage to support different performance, scaling, and cost requirements.

Teams typically choose between:

Relational databases for structured business data

NoSQL databases for high-volume or flexible data models

Object storage for files, media, and backups

These services are usually managed by the cloud provider, which simplifies scaling and backups but requires careful planning around access control and ongoing costs.

CI/CD, monitoring, and logging tools

Operating cloud systems requires constant visibility into system behavior and automated ways to release changes safely.

Most teams adopt:

CI/CD tools to automate testing and deployment

Monitoring platforms to track system health and performance

Centralized logging systems to investigate failures and usage patterns

These tools do not change application features directly, but they strongly influence how reliably teams can ship updates and diagnose production issues.

Benefits of cloud application development for businesses

Cloud adoption is often justified on technical grounds, but its impact is most visible in how businesses control costs, deliver software, manage risk, and operate at scale. These benefits are usually the deciding factors when teams compare cloud-based development with traditional approaches.

Cost structure advantages

Cloud platforms replace large upfront infrastructure purchases with usage-based spending. Organizations pay for computing, storage, and network resources as they are consumed, rather than sizing hardware for peak demand in advance.

This reduces capital expenditure and allows costs to rise or fall with actual usage. The trade-off is that spending becomes variable, which requires ongoing monitoring and budgeting discipline.

Faster development cycles

Cloud environments remove many of the delays associated with setting up infrastructure. Development and testing environments can be created in minutes, and deployment processes are typically automated.

This shortens the time between planning and release, allowing teams to validate ideas earlier and adjust direction without restarting projects or expanding operational staff.

Built-in availability features

Most cloud platforms include redundancy, traffic routing, and automated recovery mechanisms as standard capabilities.

Applications benefit from:

Multiple server instances running in parallel

Automatic replacement of failed components

Load balancing across traffic sources

These features reduce the engineering effort required to achieve basic service reliability and lower the operational risk of outages.

Global accessibility

Cloud providers operate data centers in multiple geographic regions, allowing applications to run closer to end users.

This makes it easier to serve customers across countries, support regional demand spikes, and meet data residency requirements without building separate infrastructure in each location.

Data analytics capabilities

Cloud platforms simplify the collection and processing of operational and user data.

Organizations commonly gain access to:

Centralized data storage across services

Managed analytics and reporting tools

Built-in integration with machine learning systems

This lowers the barrier to running large-scale analysis and supports faster business and product decisions.

Automatic updates and maintenance

Many infrastructure components are maintained by the cloud provider, including hardware replacements, operating system updates, and core security patches.

This reduces routine operational workload and limits the risk of systems falling behind on critical updates, although application code and configuration remain the responsibility of the development team.

Security responsibilities in cloud application development

Security in cloud environments is often misunderstood because responsibility is shared between the provider and the application team. Many incidents occur not because cloud platforms are insecure, but because teams assume the provider covers more than it actually does. Understanding where responsibility starts and ends is critical when evaluating risk.

The shared responsibility model

Cloud providers secure the underlying infrastructure, including physical data centers, networking, and the virtualization layer. Everything above that layer remains the responsibility of the organization building the application.

In practice, this means teams are responsible for application code, data handling, access controls, network configuration, and how cloud services are used. The provider supplies secure building blocks but does not enforce how they are assembled.

Common cloud security risks

Most cloud security issues stem from configuration and operational mistakes rather than platform flaws.

Typical risk areas include:

Overly permissive access policies

Publicly exposed storage or databases

Unpatched application dependencies

Hard-coded credentials in source code

Insecure service-to-service communication

These risks increase as systems grow more distributed and involve more managed services.

Identity and access management

Identity systems control who and what can access cloud resources. Weak access controls are one of the most common causes of breaches.

Effective setups usually enforce role-based access, short-lived credentials for services, and strict separation between development, testing, and production environments. Access policies should be reviewed regularly as teams and systems change.

Data protection practices

Protecting data requires more than encrypting storage.

Teams typically implement:

Encryption for data at rest and in transit

Segmentation between sensitive and non-sensitive datasets

Regular backups and recovery testing

Data retention and deletion policies

These measures reduce exposure during incidents and help meet regulatory obligations.

Monitoring and incident response basics

Cloud systems generate large volumes of logs and metrics that can be used to detect abnormal behavior.

Basic security operations usually include centralized logging, automated alerts for suspicious activity, and documented response procedures for isolating compromised resources. Without these controls, incidents often go unnoticed until customer impact occurs.

In practice, teams rely on a small set of proven cloud-native system design patterns to manage service communication, failures, and data consistency at scale.

Security in cloud development is therefore an ongoing operational responsibility, not a one-time configuration task.

Trade-offs and technical challenges to consider

Cloud application development offers clear advantages, but it also introduces constraints that affect long-term flexibility, cost control, and system reliability. Teams evaluating this approach should understand these risks early, since many of them become harder to reverse after an application is in production.

Vendor lock-in

Cloud platforms provide many proprietary services for databases, messaging, monitoring, and identity management. While these services reduce setup effort, they can make it difficult to move an application to another provider later.

Switching platforms often requires redesigning parts of the system, retraining teams, and migrating data at scale. Organizations that expect to change providers or operate across multiple clouds usually need to plan for this from the architecture stage.

Cost unpredictability

Usage-based pricing makes it easy to start small, but costs can rise quickly as traffic grows or workloads change.

Common sources of unexpected spending include:

Increased data transfer between services

Overprovisioned compute resources

Long-running background processes

Unmonitored development and testing environments

Without active cost tracking and periodic reviews, cloud spending can drift far beyond initial estimates.

Performance variability

Cloud infrastructure is shared across many customers. While providers offer strong baseline performance, factors such as noisy neighbors, network routing, and regional capacity constraints can affect response times.

Applications that require consistently low latency or predictable throughput often need additional engineering work, such as caching strategies, regional deployments, or dedicated resource allocation.

Debugging complexity

Cloud applications are usually distributed across multiple services, databases, and regions. Failures rarely occur in a single place.

Tracing errors often requires correlating logs, metrics, and events from several systems. This increases the importance of monitoring and structured logging but also raises the skill level needed to diagnose production issues quickly.

Compliance challenges

Regulated industries must meet requirements around data location, access control, audit trails, and retention policies.

While cloud providers supply compliance tools, responsibility for correct configuration remains with the organization. Misconfigured permissions or storage policies are common sources of regulatory risk.

Operational overhead

Cloud platforms reduce hardware management, but they do not eliminate operational work.

Teams still manage:

Deployment pipelines

Access control and security policies

Monitoring and alerting

Capacity planning

Incident response

In practice, cloud shifts operational effort rather than removing it, and organizations need staff with experience in distributed systems and platform management to run applications reliably.

Cost factors that influence cloud application development

Cloud pricing is often described as pay for what you use, but in practice total cost depends on many technical choices made during design and operation. Teams evaluating cloud development should understand these drivers early, since they shape both short-term budgets and long-term operating expenses.

Compute usage

Compute costs come from running application code on virtual machines, containers, or serverless functions. Pricing is usually based on time, memory allocation, and CPU usage.

Applications with steady traffic tend to generate predictable compute bills, while systems with spikes or background processing can see large swings. Architecture choices, such as always-on services versus event-driven workloads, directly affect this category.

Storage costs

Cloud platforms charge separately for storing data and for how often it is accessed.

Typical cost components include:

Database storage for transactional data

Object storage for files and backups

Read and write operation charges

Long-term archival tiers

Poor data lifecycle management often leads to unnecessary growth in this area over time.

Network traffic

Moving data between services, regions, or out of the cloud provider’s network generates additional charges.

This is easy to underestimate during planning, especially for applications that rely heavily on APIs, media delivery, or cross-region replication. Network costs often increase as user bases grow or systems become more distributed.

For example, video streaming platforms and API-heavy mobile apps often find that data transfer becomes one of their largest monthly cloud expenses.

Managed services

Databases, message queues, analytics platforms, and identity services simplify development, but they come with their own pricing models.

While these services reduce operational effort, they usually cost more than self-managed alternatives and can become a significant portion of monthly spending as usage scales.

DevOps and monitoring expenses

Operating cloud systems requires tooling for deployment automation, logging, metrics, and alerting.

Organizations typically pay for:

CI/CD platforms

Monitoring and observability services

Log storage and analysis tools

These costs are indirect but essential for maintaining reliability and diagnosing issues in distributed environments.

Long-term operational costs

Beyond infrastructure, cloud applications incur ongoing human and process costs.

These include:

Platform engineering and operations staff

Security reviews and compliance audits

Regular architecture and cost optimization work

Incident response and system upgrades

Over time, these expenses often exceed initial development costs and should be included in any realistic financial planning.

Best practices for building reliable cloud applications

Reliability in cloud systems is rarely the result of a single tool or platform feature. It comes from a set of engineering practices that reduce failure impact, limit configuration errors, and make systems easier to operate as they grow.

Fault tolerance strategies

Cloud infrastructure is designed to fail in small ways, such as individual servers restarting or network routes changing. Reliable applications are built to expect this.

Common approaches include running multiple instances of critical services, designing stateless components where possible, and isolating failures so that one service does not bring down the entire system. These patterns reduce downtime but require careful planning around data consistency and service dependencies.

Infrastructure as code

Infrastructure as code treats servers, networks, and cloud services as versioned configuration files rather than manual setup tasks.

This allows teams to recreate environments consistently, review changes before they are applied, and roll back infrastructure updates when problems occur. It also reduces configuration drift between development, testing, and production systems.

Organizations without in-house platform expertise often rely on cloud infrastructure developers to design and maintain these environments.

Environment separation

Cloud projects typically maintain separate environments for development, testing, and production to limit the impact of mistakes.

Effective setups usually include:

Isolated cloud accounts or projects

Separate databases and storage resources

Restricted access to production systems

This separation reduces the risk that experimental changes affect live users and supports safer testing of new features.

Observability

Distributed systems are difficult to troubleshoot without detailed visibility into what is happening internally.

Observability usually combines metrics, logs, and traces to show how requests move through the system and where failures occur. Teams that invest in structured logging and meaningful metrics resolve incidents faster and avoid relying on guesswork during outages.

Testing automation

Manual testing does not scale well in environments where applications are updated frequently.

Automated test suites commonly include unit tests, integration tests, and security checks that run on every change. This helps catch regressions early and reduces the chance that faulty code reaches production.

Deployment strategies

How updates are released affects both stability and recovery time.

Teams often rely on:

Rolling deployments to update services gradually

Blue-green releases to switch traffic between versions

Feature flags to control exposure of new functionality

These approaches limit user impact when issues occur and make it easier to reverse problematic changes without extended downtime.

Real-world use cases for cloud applications

Cloud development choices become clearer when viewed through actual application types. Different use cases place different demands on scalability, reliability, data handling, and long-term operations.

SaaS platforms

SaaS products use cloud infrastructure to deliver the same application to many customers while keeping data logically separated. These systems depend on managed databases, identity services, and automated deployments to support frequent updates and tenant isolation.

Cloud environments make it easier to onboard new customers, release features continuously, and scale capacity without redesigning the system.

Internal enterprise systems

Organizations often move internal tools such as reporting systems, HR platforms, and workflow applications to the cloud to reduce infrastructure maintenance and improve remote access.

Common characteristics include:

Integration with identity providers and legacy systems

Centralized access control

Secure access from multiple locations

These systems benefit from predictable workloads and easier integration with other cloud-based services.

Consumer applications

Mobile apps, e-commerce platforms, and content services rely on cloud infrastructure to handle unpredictable traffic and regional usage spikes.

Cloud platforms allow these applications to distribute traffic across locations, store large media assets, and recover quickly from localized failures without manual intervention.

Data processing platforms

Data platforms use cloud services to ingest, store, and analyze large volumes of information from applications, users, and connected systems.

Typical workloads include:

Log and event processing

Business intelligence pipelines

Machine learning training jobs

Batch data transformations

A common example is an analytics pipeline that processes application logs overnight to generate daily usage and performance reports.

Elastic computing and storage make these short-term, high-intensity workloads economically viable.

IoT backends

IoT systems use cloud services to receive data from large numbers of devices and send control messages back to them.

These backends must handle unreliable connectivity, high message volumes, and long-term data retention. Cloud platforms simplify device authentication, message routing, and horizontal scaling as device counts grow.

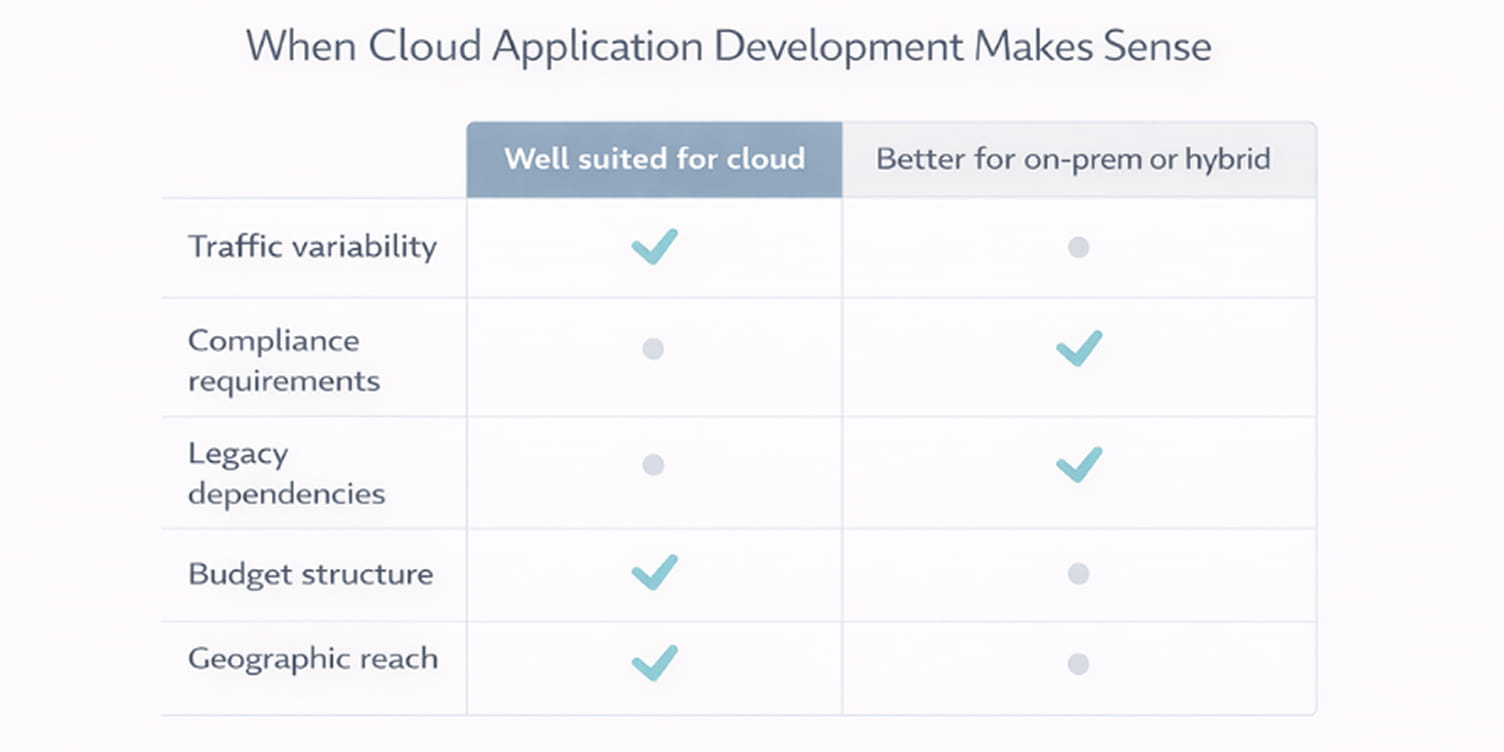

When cloud application development is the right choice and when it is not

Cloud adoption is often presented as a default path, but it is not universally suitable. The right decision depends on how the business operates, what the application must support, and which constraints exist around cost, regulation, and technical risk.

Business scenarios suited for cloud

Cloud development is typically a strong fit when organizations need flexibility, faster delivery, or variable capacity.

Common scenarios include:

SaaS products serving multiple customers

Applications with unpredictable or seasonal traffic

Products requiring frequent updates or experimentation

Systems used by geographically distributed teams or customers

Projects that benefit from managed databases, messaging, or analytics services

In these cases, the ability to provision resources quickly and adjust capacity without long planning cycles usually outweighs the added operational complexity.

Situations better served by on-prem or hybrid environments

Some workloads perform better outside a fully public cloud setup.

Organizations often choose on-prem or hybrid approaches when applications depend on legacy systems, require consistent low-latency access to local data, or must remain operational even if external connectivity is limited. Hybrid models are also common when sensitive workloads must stay isolated while customer-facing components run in the cloud.

Technical and regulatory constraints

Certain technical and legal requirements limit how cloud platforms can be used.

These commonly include:

Data residency laws requiring storage in specific locations

Industry regulations with strict audit or access controls

Dependencies on specialized hardware or proprietary systems

Performance requirements that cannot tolerate shared infrastructure

While cloud providers offer compliance tools, responsibility for correct configuration and validation remains with the organization.

Budget considerations

Cloud development reduces upfront infrastructure investment but introduces ongoing operating costs.

For small or experimental projects, this model lowers financial risk. For stable, high-volume systems with predictable workloads, long-term cloud costs can exceed the price of owning infrastructure. Teams should evaluate not only development cost but also multi-year operating expenses, staffing needs, and compliance overhead.

In practice, many organizations adopt a mixed approach, using cloud platforms where flexibility provides clear value and retaining traditional environments where constraints make them more economical or reliable.

Conclusion

Cloud application development is not a single technology choice but a series of architectural, operational, and financial decisions that shape how software behaves over its entire lifecycle. The difference between a system that scales smoothly and one that becomes fragile often comes down to how deliberately these early choices are made.

Understanding service models, architecture patterns, security responsibilities, cost drivers, and operational practices makes those decisions predictable instead of experimental. It allows teams to trade short-term convenience against long-term reliability, compliance, and control with clear expectations.

For organizations evaluating this path, the goal is not to follow trends but to match the development approach to real business needs, technical constraints, and long-term operating realities. When that alignment exists, cloud platforms become a foundation for steady growth rather than a source of ongoing risk.