Healthcare Software Development: Process, Cost, and Challenges

Healthcare software projects fail for predictable reasons: unclear requirements, regulatory blind spots, weak user adoption, and underestimated complexity. Teams often start with a feature list but overlook how clinical workflows, data protection, and system integration reshape every technical decision.

According to the U.S. Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC), 96% of non-federal acute care hospitals now use certified electronic health record systems, reflecting the scale at which software must work

This guide explains how healthcare software development works from planning to deployment. You’ll learn the main types of healthcare systems, the development process, compliance requirements, technical choices that affect risk and cost, common failure patterns, and how to evaluate development partners with confidence.

Definition and scope of healthcare software development

Teams planning a healthcare software project need more than a generic understanding of application development. Regulatory exposure, data sensitivity, and system dependencies fundamentally change how software must be designed, built, and operated in this sector.

Understanding what qualifies as healthcare software, how different system types are defined, and where this work fits within health technology helps avoid incorrect scoping and unrealistic expectations early in the project.

This section establishes those boundaries.

What qualifies as healthcare software

Healthcare software includes any system that creates, processes, stores, or exchanges medical or health-related data or directly supports care delivery and healthcare operations.

In practice, this includes software that:

Manages patient medical records or treatment history

Supports diagnosis, clinical decision-making, or patient monitoring

Enables communication between patients, providers, laboratories, or insurers

Integrates with medical devices or hospital infrastructure

Processes billing, insurance claims, or regulatory reporting tied to healthcare services

If a system affects patient care, clinical workflows, or regulated health data, it falls under healthcare software development and must meet stricter standards than general business applications.

Healthcare applications, clinical systems, and administrative platforms

Healthcare software is often discussed as a single category, but it spans three distinct system types with different technical and regulatory implications.

Healthcare applications

These are user-facing tools used by patients or clinicians, such as telemedicine apps, appointment scheduling platforms, symptom trackers, and medication management tools.

Their primary focus is accessibility and usability, but they still handle protected health information and require secure data handling.

Clinical systems

These form the operational core of care delivery. Examples include electronic health records, laboratory information systems, imaging platforms, and clinical decision support tools.

They manage structured medical data and directly influence diagnosis and treatment, making reliability and data integrity critical.

Administrative platforms

These support the business and compliance side of healthcare organizations. Billing systems, insurance claims platforms, resource management tools, and regulatory reporting software fall into this category.

While patients may never interact with them, failures can disrupt revenue, compliance, and legal standing.

Identifying which category a product belongs to determines the project’s compliance scope, integration requirements, testing depth, and long-term maintenance burden.

Where healthcare software development fits within health technology

Healthcare software development operates within a broader health technology ecosystem that includes software built for teams developing a medical device, hospital infrastructure, data platforms, and insurance systems.

What distinguishes it from most other software fields are three constant constraints:

Legal responsibility for patient data and safety

Mandatory interoperability with external clinical and insurance systems

Long operational lifecycles that require ongoing compliance updates and audits

As a result, healthcare software projects prioritize stability, traceability, and regulatory alignment over rapid experimentation. For decision-makers, this scope directly affects budgeting, staffing requirements, vendor selection, and delivery timelines.

Major categories of healthcare software systems

Healthcare software is not a single product type. The category a system falls into determines its regulatory exposure, integration requirements, development timeline, and long-term operating cost.

For teams evaluating a project, identifying the correct class of software early helps narrow technical options and prevents designing for the wrong constraints.

Clinical systems

Clinical systems support diagnosis, treatment, and care delivery. They operate at the center of medical workflows and manage structured patient data.

Common examples include

Electronic health records (EHR) and electronic medical records (EMR)

Laboratory information systems

Imaging and radiology platforms

Clinical decision support tools

These platforms must maintain high data accuracy, preserve audit trails, and integrate with external providers, pharmacies, and diagnostic services, which is why understanding EHR and EMR integration costs becomes important when evaluating project budgets.

Even minor failures can affect patient safety or clinical outcomes, which places strong requirements on validation, testing, and controlled system changes.

Patient-facing applications

Patient-facing applications are designed for direct use by patients outside clinical settings.

Typical use cases include:

Appointment scheduling and patient portals

Medication reminders and adherence tracking

Symptom reporting and post-treatment monitoring

Secure communication with care teams

Although these systems often appear simpler than clinical platforms, they still handle protected health information and must support identity verification, secure data storage, and reliable synchronization with clinical records.

Usability becomes a core technical constraint because poor adoption directly limits clinical value and operational return.

Telemedicine platforms

Telemedicine systems enable remote consultations, diagnostics, and follow-up care through video, messaging, and connected devices.

They combine characteristics of patient applications and clinical systems while introducing additional infrastructure requirements such as secure video communication, provider credential verification, prescription workflows, and integration with electronic health records. In practice, reliability during peak usage and continuity of medical data matter more than incremental feature expansion.

Hospital and operations software

Hospital and operations software supports internal coordination within healthcare organizations rather than direct patient interaction.

This category typically includes systems for:

Staff scheduling and shift management

Bed and capacity planning

Operating room coordination

Inventory and supply chain tracking

These platforms are often customized to existing hospital processes and deeply integrated with clinical systems. While errors rarely affect diagnosis directly, they can disrupt staffing levels, patient throughput, and facility utilization at scale.

Billing and insurance systems

Billing and insurance systems manage financial transactions between providers, patients, and payers.

They handle medical coding validation, claims submission, reimbursement tracking, and audit documentation. Design priorities center on accuracy, traceability, and regulatory compliance because failures frequently lead to delayed payments, disputes with insurers, or regulatory scrutiny.

Research and data platforms

Research and data platforms support clinical studies, population health analysis, and institutional reporting.

They aggregate information from multiple clinical and administrative systems and apply governance rules to control access and usage. Development emphasis is usually placed on data standardization, long-term integrity, auditability, and compliance with research protocols rather than interface complexity.

Each category serves a different function, operates under a different risk profile, and requires a different level of regulatory oversight. Correct classification is a prerequisite for realistic budgeting, architecture planning, and development timelines.

Healthcare software development process

Healthcare software projects succeed or fail long before the first line of code is written. Decisions made during planning, compliance setup, and system design determine whether a product can be approved for use, integrated into clinical workflows, and maintained safely over time.

The process below reflects how healthcare systems are typically built in practice, with constraints that do not apply to most other software domains.

Problem definition and requirements gathering

The first stage is defining what problem the system is meant to solve and who will use it. In healthcare, this usually involves multiple stakeholders: clinicians, administrators, compliance officers, IT teams, and sometimes patients.

Requirements are documented in far more detail than in consumer software projects. Teams must specify data types, workflows, reporting needs, integrations with existing systems, and failure scenarios. Ambiguous requirements often surface later as compliance gaps or workflow breakdowns, which are costly to correct after deployment.

Regulatory planning

Regulatory planning begins alongside requirements gathering, not after development.

Teams determine which privacy, data protection, and healthcare regulations apply based on:

The type of data being processed

The role of the system in patient care

The jurisdictions in which it will operate

This stage influences data storage design, access controls, audit logging, and documentation practices. Skipping or postponing regulatory analysis often leads to rework during testing or certification reviews.

UX design for medical and patient users

User experience design in healthcare serves two different audiences: clinical staff and patients.

Clinicians need interfaces that reduce cognitive load, minimize manual data entry, and align with established medical workflows. Patients need clarity, accessibility, and predictable behavior, often across devices and varying levels of technical literacy.

Design decisions at this stage affect training time, adoption rates, error frequency, and long-term operational cost. Prototypes are commonly reviewed with representative users before development begins.

System architecture

Architecture planning defines how data moves through the system and how components interact.

This typically includes decisions around:

Centralized versus distributed data storage

Integration methods with existing hospital or insurance systems

Identity and access management models

Backup and recovery strategies

In healthcare, architecture choices are tightly linked to compliance obligations and future interoperability requirements. Overly rigid designs make later regulatory changes or integrations difficult to implement.

Development stages

Development usually follows an incremental model with controlled releases rather than rapid, feature-heavy iterations.

Core clinical functionality and data handling components are implemented first, followed by secondary workflows and reporting tools. Documentation is produced alongside code to support audits, security reviews, and handover to operations teams.

Changes are often gated through formal review processes, particularly for systems that affect diagnosis, treatment, or billing.

Testing approaches

Testing in healthcare software extends well beyond functional validation.

Projects typically include:

Security testing to identify data exposure risks

Integration testing with external clinical and billing systems

Performance testing under peak usage conditions

Validation against regulatory requirements and documentation standards

Testing artifacts are commonly retained as part of compliance records and may be reviewed during audits or certification processes.

Deployment and long-term maintenance

Deployment is treated as a controlled operational event rather than a simple release.

Organizations plan for data migration, staff training, rollback procedures, and staged rollouts to reduce disruption to clinical services. After launch, maintenance becomes an ongoing responsibility that includes:

Security updates

Regulatory changes

System monitoring and incident response

Periodic revalidation of integrations

Unlike consumer software, healthcare systems are often expected to remain in service for many years, which makes long-term support planning part of the original development scope.

Regulatory, privacy, and data protection requirements

Regulation is not a secondary concern in healthcare software development. It shapes system architecture, data handling practices, access control, and operational procedures from the earliest design stages. Teams that postpone compliance planning often face redesigns, delayed deployments, or rejection during vendor evaluations.

Core privacy principles

Most healthcare regulations are built on consistent privacy foundations: collect only necessary data, restrict access to authorized users, document how information is used, and allow patients to review or correct their records.

From a system design perspective, this typically translates into role-based access control, detailed activity logs, consent tracking, and controlled data sharing. These capabilities affect how databases, APIs, and user permissions are structured.

Healthcare data protection obligations

Healthcare software must protect sensitive data across its full lifecycle, including transmission, storage, backup, and deletion.

In practice, this usually involves:

Encryption for stored and transmitted data

Strong user authentication and session controls

Separation of sensitive datasets from general system data

Documented backup and recovery procedures

These safeguards must be implemented consistently across development, testing, and production environments to withstand security reviews.

This is especially true for systems deployed on public cloud infrastructure, where weaknesses in healthcare data security in cloud environments are a common source of regulatory risk.

Regulatory frameworks commonly involved

The specific rules depend on geography and system purpose, but healthcare projects commonly fall under multiple overlapping regulatory regimes covering health data privacy, medical software safety, financial transactions, and breach reporting.

These frameworks influence architecture decisions, documentation requirements, and internal approval processes. Compliance is demonstrated through traceable system records and development history, not statements of intent.

Audit readiness

Healthcare systems should be designed with the assumption that they will be examined by internal or external auditors.

This means maintaining:

Clear documentation of system architecture and data flows

Records of security controls and access policies

Version histories and approved change logs

Evidence of testing and validation

Generating these artifacts during development is significantly less disruptive than reconstructing them after deployment.

Consequences of non-compliance

Non-compliance creates operational risk beyond regulatory fines.

Organizations may face delayed launches, forced system shutdowns, mandatory remediation projects, or loss of contracts with providers and insurers. Rebuilding a system under regulatory pressure is often more expensive than designing it correctly from the start.

For teams evaluating a healthcare software initiative, compliance requirements directly affect technical scope, staffing needs, timelines, and total cost of ownership.

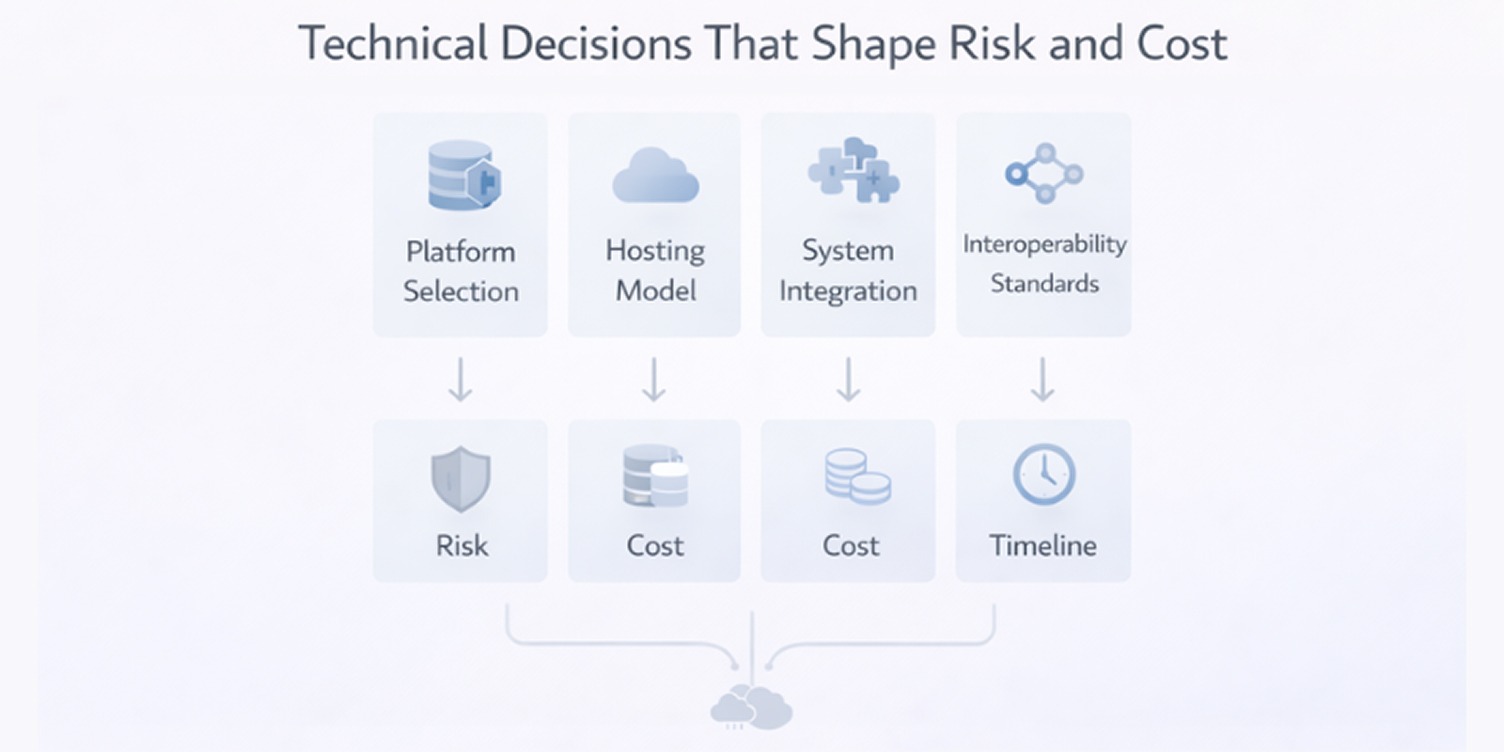

Technical decisions that influence risk, cost, and timeline

In healthcare software projects, early technical decisions shape far more than system performance. They influence regulatory effort, integration complexity, development duration, and long-term operating cost.

These choices are difficult to reverse once development starts, which makes them part of risk management, not just engineering preference.

Platform selection

Platform choice determines how users access the system and how updates, security controls, and support are handled.

Most projects fall into three broad options:

Web-based systems for clinical and administrative users

Mobile applications for patient-facing use cases

Cross-platform solutions that share code across environments

Web platforms simplify rollout across hospitals and reduce device management. Mobile apps support notifications, offline access, and hardware features. Cross-platform tools shorten initial development but can limit flexibility later.

The right choice depends on user context, compliance expectations, and how often the system must change.

Hosting models

Infrastructure decisions affect compliance scope, operating cost, and failure recovery. Cloud hosting reduces infrastructure management and simplifies disaster recovery but requires strict control over shared security responsibilities.

On-premises deployment offers tighter control over data location and access policies, at the cost of higher staffing and capital investment. Hybrid setups are common when sensitive data must remain local while other services operate remotely.

These trade-offs directly influence both budget planning and long-term support requirements.

Integration with existing systems

Healthcare software rarely operates in isolation. Most platforms must exchange data with electronic health records, laboratory systems, billing software, and identity providers. Each integration introduces new dependencies, testing effort, and potential failure points.

Projects frequently miss timelines not because the core system is incomplete, but because integration work expands late in development.

Interoperability standards

Interoperability standards define how structured medical data is exchanged between systems.

Standards such as HL7 and FHIR affect:

Database design

API structure

Validation logic

Documentation requirements

Supporting them early increases design effort but simplifies onboarding with hospitals and insurers later. Skipping them may reduce short-term cost while limiting adoption and increasing future integration work.

Build versus buy considerations

Not every component should be built internally. Teams often evaluate third-party solutions for areas like identity management, video consultations, payment processing, or clinical terminology services.

Building offers full control but increases regulatory exposure and development time. Buying shortens delivery but introduces licensing costs and vendor dependency.

This decision should be driven by regulatory risk, system criticality, and total ownership cost, not just speed.

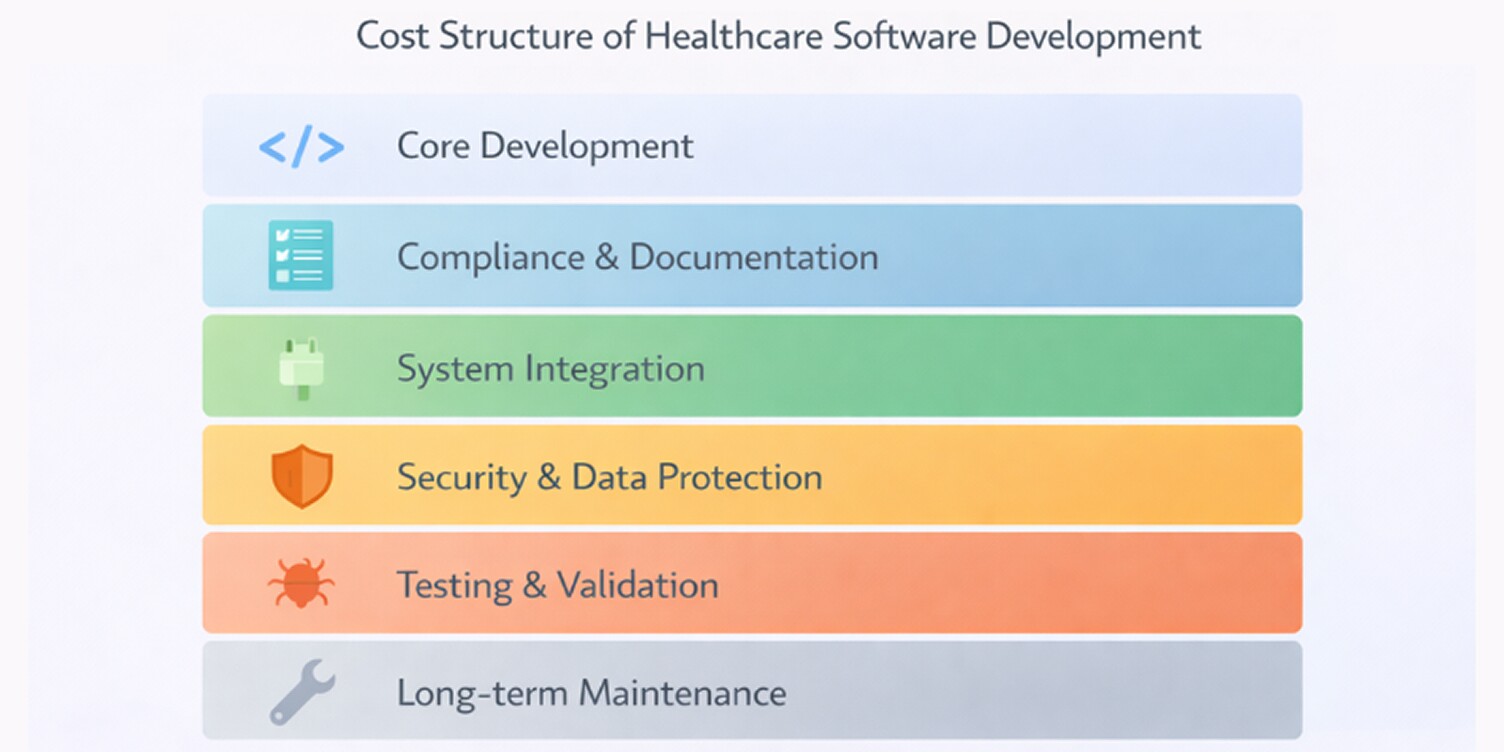

Cost structure of healthcare software development

Healthcare software budgets often exceed early estimates because cost is shaped by more than feature count. Regulatory scope, integration depth, data sensitivity, and long-term support requirements all influence total investment. Understanding how costs are distributed helps teams plan realistically and avoid underfunding critical areas.

Development cost varies significantly by system category. The ranges below reflect typical projects in regulated healthcare environments and exclude long-term infrastructure and maintenance expenses.

Healthcare software cost by system type (Development only)

Actual budgets often exceed these ranges once integrations, compliance documentation, validation cycles, and post-launch support are included.

Key cost drivers

Several factors consistently account for most healthcare software spending. Regulatory requirements increase engineering time through documentation, validation, and security controls. Integration with external systems adds testing cycles and coordination effort.

Data protection measures raise infrastructure and development costs. Finally, domain expertise is more expensive than general software labor, particularly for clinical workflow design and compliance engineering. Together, these elements often outweigh the cost of building core features.

For this reason, many organizations assess different software outsourcing models in regulated projects to understand how compliance effort, integration work, and long-term support are distributed across vendors.

Factors that increase project complexity

Certain conditions push projects into higher cost brackets even when the feature scope appears modest. This commonly includes multi-system integrations, support for multiple regions or regulatory frameworks, real-time data exchange with clinical devices, and workflows that must mirror existing hospital processes.

Migration from legacy systems is another major cost amplifier, especially when data quality is inconsistent or poorly documented. Complexity rarely appears in project specifications but surfaces during design and testing.

Ongoing maintenance and compliance costs

Healthcare software is not a one-time expense.

After launch, organizations should plan for:

Security updates and vulnerability management

Regulatory changes and periodic compliance reviews

Infrastructure hosting and monitoring

Integration maintenance as external systems evolve

User support and operational troubleshooting

Annual maintenance commonly ranges from 15% to 30% of the original development cost. Systems involved in clinical decision-making or billing often sit at the higher end of that range due to audit preparation and validation requirements.

Common causes of failure in healthcare software projects

Many healthcare software projects fail despite adequate funding and technically capable teams. The underlying causes are rarely technical alone. Most failures stem from predictable gaps in planning, design, compliance, and organizational readiness. Recognizing these patterns early helps teams reduce risk before problems become expensive to correct.

Regulatory oversights

Compliance failures usually begin long before audits or certification reviews. Projects run into trouble when privacy rules, data retention policies, and audit requirements are treated as documentation tasks instead of system design constraints.

Teams often underestimate how deeply regulation affects data models, access control, logging, and system architecture.

Common early mistakes include:

Defining compliance requirements after development has started

Designing workflows that conflict with audit or reporting obligations

Underestimating documentation and validation effort

These issues typically lead to architectural rework, delayed approvals, or restricted deployment environments. In healthcare, technical correctness alone is not sufficient for system acceptance.

Poor user experience design

Healthcare users operate under time pressure and high cognitive load. Interfaces that require excessive navigation, duplicate data entry, or unclear workflows are frequently bypassed or used incorrectly. Clinicians revert to manual processes, and patients abandon applications that feel confusing or unreliable.

Adoption failures are often labeled as training problems, but they usually originate in early design decisions that did not account for real clinical workflows or patient behavior.

Incomplete requirements

Projects frequently begin with feature lists instead of operational definitions. Missing edge cases, undocumented workflows, and vague integration assumptions surface during testing or early deployment.

At that stage, changes are slower, more expensive, and risk destabilizing already validated components. In healthcare environments, incomplete requirements often create both functional defects and compliance gaps, compounding their impact.

Security gaps

Security failures do not always involve public data breaches.

Many projects encounter issues during audits or third-party assessments due to:

Weak role-based access control

Inconsistent encryption practices

Limited monitoring and incident detection

Even without confirmed data loss, these weaknesses can violate regulatory obligations and force emergency remediation under strict timelines. Retrofitting security controls after deployment is consistently more expensive than designing them from the start.

Operational adoption challenges

Technically sound systems still fail if they do not align with how healthcare organizations actually function. Hospitals and clinics operate with rigid schedules, staffing constraints, and established routines. Software that requires significant behavioral change without structured transition planning meets resistance.

Delays in training, unclear system ownership, and lack of operational support frequently lead to partial adoption or complete abandonment, regardless of technical quality.

Criteria for selecting a healthcare software development partner

Choosing a development partner in healthcare is as much a risky decision as a technical one. The vendor you select will influence compliance outcomes, delivery timelines, system reliability, and long-term support costs.

Evaluating providers only on hourly rates or generic portfolios often leads to problems that surface after contracts are signed.

Technical capabilities to assess

A healthcare partner must demonstrate more than general software proficiency. You should look for evidence of experience with complex system architecture, secure data handling, integration-heavy projects, and long-term system maintenance. Teams should be comfortable working with structured data models, versioned APIs, and controlled release processes.

Projects that include patient portals, remote monitoring, or telehealth workflows often require dedicated mobile application development teams familiar with healthcare security controls and identity-management constraints.

Healthcare domain experience

Healthcare workflows differ significantly from other industries. Partners with domain experience understand how clinicians work, how hospitals operate, and how administrative systems interact with care delivery. This reduces the risk of building workflows that look correct on paper but fail in real clinical settings.

Domain familiarity also shortens requirements gathering because teams recognize common patterns in scheduling, documentation, billing, and patient communication.

Many organizations start by reviewing shortlists of custom healthcare software development companies to compare regulatory experience, integration capability, and long-term support models before entering technical discussions.

Compliance expertise

Regulatory knowledge should exist within the delivery team, not only at a consulting level. Practical indicators include experience preparing systems for audits, producing compliance documentation, implementing access controls, and supporting data retention policies.

Vendors should be able to describe how compliance requirements influence architecture and development practices, not just reference regulations by name. Weak compliance capability often leads to expensive redesigns late in the project.

Communication and delivery practices

Healthcare projects involve multiple stakeholders and formal review cycles.

Reliable partners typically demonstrate:

Structured requirements documentation

Clear change management procedures

Regular progress reporting tied to measurable milestones

Without these practices, small misunderstandings compound into missed deadlines and scope disputes, especially once compliance reviews begin.

Contract and ownership considerations

Contract structure directly affects long-term control of the system. Teams should clarify ownership of source code, data models, and documentation, along with rights to modify or transfer the system in the future.

Support obligations, security responsibilities, and response times for critical incidents should be explicitly defined. In healthcare environments, vague ownership or support terms can become operational risks when systems are audited, transferred, or expanded.

Measuring Success After Deployment

Launching healthcare software is an operational milestone, not proof of success. Real value shows up when the system is consistently used, trusted by staff, compliant with regulations, and economical to operate over time.

Measuring outcomes after deployment helps teams catch problems early and decide whether the system is delivering what it was built for.

Product adoption metrics

Adoption is the first signal that the software fits real workflows.

Teams typically track:

Active users as a percentage of total users

Login frequency and session duration

Completion rates for key tasks

Feature usage patterns over time

For patient-facing systems, missed appointments, repeat usage, and response rates to messages are equally telling. Low adoption usually points to workflow friction or poor usability, not user unwillingness.

Clinical and operational indicators

Usage alone does not prove impact. Clinical indicators often focus on whether the system reduces documentation time, lowers error rates, or improves access to patient information.

Operational indicators look at scheduling efficiency, billing turnaround time, or staff workload distribution. These measures show whether the software improves care delivery or simply digitizes existing problems.

System reliability and data quality

Reliability determines whether clinicians trust the system during daily work.

Common technical indicators include:

System uptime and outage frequency

Average response times

Data synchronization delays between integrated platforms

Error rates in critical workflows

Data quality is equally important. Inconsistent or incomplete records quickly undermine confidence, even if the application itself is stable.

Compliance performance

Regulatory compliance must hold after launch, not just during approval. Organizations monitor audit outcomes, access violations, incident response timelines, and documentation completeness.

Systems that technically function but fail compliance checks introduce operational risk, regardless of feature depth. Strong compliance performance usually reflects disciplined development and change management practices.

Long-term cost efficiency

Healthcare software produces returns over years, not quarters. Teams assess support workload, infrastructure costs, frequency of emergency fixes, and the effort required to implement regulatory updates.

Systems that demand constant reactive maintenance drain budgets without improving outcomes. Stable operating costs indicate that architecture and delivery decisions were realistic from the start.

Key takeaways for decision-makers

At the end of most healthcare software initiatives, outcomes depend less on technical features and more on how well risk, compliance, and operational reality were handled from the start. Successful systems are rarely the most ambitious. They are the ones designed around regulatory constraints, integration depth, and long-term use inside real organizations.

Choosing a development partner is therefore less about finding the fastest team and more about finding one aligned with how healthcare systems actually function and evolve.

Principles that lead to durable healthcare software

The following principles consistently separate stable, long-lived healthcare platforms from projects that struggle after launch.

Compliance must shape architecture, not documentation

Regulatory requirements influence data models, access control, logging, and release processes. Treating compliance as paperwork instead of a design input usually results in rework or deployment delays.

Integration effort dominates timelines

Most healthcare systems succeed or fail based on how well they connect to EHRs, billing platforms, laboratories, and identity providers. Integration complexity should be assumed, not treated as an edge case.

Workflow fit matters more than interface polish

Clinicians and administrators adopt systems that reduce friction in daily work. Even well-built software fails when it disrupts established clinical or operational routines.

Security is an operational capability, not a feature

Access control, monitoring, and incident response determine long-term risk more than individual security tools. Weak operational practices eventually surface during audits or incidents.

Maintenance cost defines true ROI

Development budgets are temporary. Compliance updates, infrastructure, integrations, and support shape the real cost of ownership over years.

Healthcare software projects that are planned around these realities tend to remain usable, compliant, and financially predictable long after initial deployment. Those that optimize primarily for speed or short-term savings often inherit technical and regulatory debt that is expensive to unwind later.

Working with Code B on healthcare software projects

Healthcare software development is primarily an exercise in risk control, not rapid feature delivery. Code B approaches healthcare systems as regulated infrastructure, with an emphasis on compliance, integration reliability, and long-term operational stability.

Where Code B is a strong fit

Code B is typically well suited for projects that involve:

Integration with existing EHR, billing, or insurance platforms

Applications handling regulated clinical or patient data

Multi-stakeholder workflows across clinical, administrative, and IT teams

Systems expected to operate for years with ongoing compliance obligations

The delivery model prioritizes structured requirements, compliance-aware architecture, and controlled release processes. This reduces late-stage redesign, audit friction, and instability during production rollouts.

Organizations evaluating long-term healthcare software development solutions often prioritize vendors with proven experience delivering systems that can pass audits, integrate reliably with hospital infrastructure, and remain stable through regulatory change.

When Code B may not be the right choice

Code B is not optimized for projects where speed and experimentation outweigh regulatory or operational constraints, including:

Lightweight prototypes with minimal compliance scope

Short-term MVPs built purely for market validation

Cost-driven projects prioritizing lowest-price delivery

Products without defined clinical or operational workflows

In these scenarios, teams designed for early-stage experimentation or rapid iteration may be a better fit than a compliance-oriented engineering partner.

Service scope and engagement model

Many healthcare platforms also depend on regulated cloud environments for data storage, interoperability, and disaster recovery, which requires experience in healthcare cloud application development services.

This end-to-end scope allows organizations to work with a single technical partner from early planning through production support, reducing coordination risk across vendors and ensuring architectural and compliance decisions remain consistent throughout the system’s lifecycle.